Graft-Versus-Host Disease by Dr. Christine Duncan.

Thank you for having me.

My name is Christy Duncan from Dana-Farber and Children's Hospital, Boston.

I'm one of the stem cell transplant physicians.

And I'm going to be talking about the most common complication of allogeneic stem cell

transplant, and that is graft-versus-host disease.

Overview of Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant.

Before jumping into the complication, I think it's important to talk about stem cell transplant,

what it is, and who we transplant, so we know who is at risk for this complication.

So stem cell transplant is the process of replacing the patient's normal bone marrow

with stem cells capable of restoring hematopoiesis, so capable of developing red blood cells,

the immune system, platelets, and all of the other stem cell components.

The marrow needs to be replaced, either because the marrow is diseased, as in leukemia, or

it's dysfunctional as in aplastic anemia, or there is a need to give high-dose chemotherapy.

Patients can receive either their own stored stem cells, which is an autologous stem cell

transplant.

Or they can receive stem cells from another person or an umbilical cord, which is an allogeneic

transplant.

The transplantable diseases fall into multiple different categories.

The first category being marrow malignancies.

So these are the leukemias of childhood, so acute lymphoblastic leukemia, acute myelogenous

leukemia, chronic myelogenous leukemia, or juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia.

Not all children with these diseases proceed to transplant, but those with high-risk disease

who are at increased risk of relapsing do frequently proceed to transplant, or those

who have relapsed often go to transplant.

We also transplant a large number of children with non-cancerous disorders.

So the first being nonmalignant hematologic diseases and bone marrow failure.

So this comprises the group of patients with a aplastic anemia, thalassemia, and sickle

cell disease.

The third category are children who are missing some component of their immune system.

And so those are children with severe combined immunodeficiency, Wiskott-Aldrich disease

or HLH, which is Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis.

And those children always receive their stem cells from another person because they are

missing a key component of their immune system.

And finally, there is a growing number of patients being transplanted for metabolic

diseases.

These include such diseases as adrenoleukodystrophy, Krabbe, and Hurler disease.

So the list on this slide incorporates mainly the categories of transplant.

It is not all-inclusive of the diseases that we transplant.

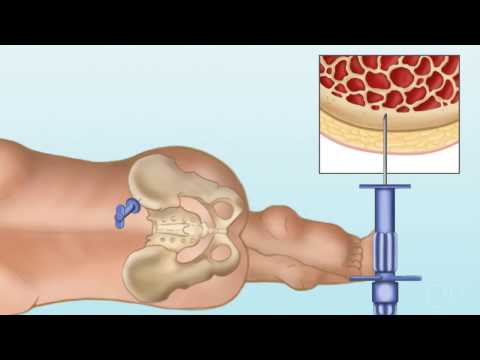

The stem cells can come from multiple different sources.

The first source, and the oldest source is bone marrow.

This is the preferred source for stem cells at most pediatric stem cell centers.

And this is because it is very rich in stem cells, and it has been used the longest.

So it is the benchmark for engraftment, graft-versus-host disease, and graft-versus-leukemia.

The bone marrow is collected in the operating room where we need approximately 10 to 15

CCs or 10 to 15 milliliters per kilogram of recipient body weight.

So for a child who weighs 10 kilograms, we need to get either 100 or 150 milliliters

of bone marrow.

The advantage is that there is no pre-donation treatment needed.

The donor does not need any vascular access.

But they do run into the risks of being in the operating room and having full anesthesia.

The picture demonstrates the process of aspirating marrow from a patient.

And so this is how it would be done in the operating room.

There would be another person on the opposite side of the iliac crest doing the same thing.

This can be challenging because what you need to do is collect that large volume of marrow,

but you could only go into the same hole in the bone once.

And so, for donors who are donating to an adult-sized person, or even a larger child,

this can mean having anywhere from 60 to 80 holes in your bone during the process of donation.

Peripheral blood stem cells are certainly easier to collect, and they do not require

operative care.

So PBSCs, or Peripheral Blood Stem Cells are gathered via peripheral apheresis.

The challenge is that peripheral blood is not rich in stem cells.

And so to increase the circulating stem cells, patients are given, subcutaneously, colony-stimulating

agents including GCSF.

PVSCs have the advantage of having the greatest graft-versus-lukemia effect.

However, they have also the highest risk of graft-versus-host disease.

A second advantage is that they tend to engraft faster.

So the period of neutropenia following the ablated conditioning is much shorter when

peripheral blood stem cells are used.

In many patients, especially within adults, that shorter neutropenic period translates

into lower transplant-related morbidity.

This all sounds very good.

However, peripheral blood stem cells are not recommended for most pediatric transplants.

The reason being that children have been shown, in a large consortium of studies, to have

an increased risk of graft-versus-host disease and faster engraftment.

But this doesn't decrease the risk of leukemia relapse.

So no increase in GVL.

So overall, using peripheral blood stem cells gives a greater risk of graft-versus-host

disease with no improvement in survival.

The third source of stem cells comes from umbilical cord blood.

So this is cord blood that is extracted from the placenta at delivery, so after the child

is delivered, either via direct drainage or direct cannulation.

The good thing about umbilical cord blood stem cells is that the umbilical cord blood

is very rich in stem cells.

A disadvantage to using this approach is that it has the slowest time to engraftment, it

has the most immunologically naive immune system, so greater risk of viruses.

It does, though, also have the lowest risk of graft-versus-host disease.

Which means you can take a person who is less well-matched and use umbilical cord from that

patient than you could with peripheral blood cells or marrow and have an equivalent graft-versus-host

disease risk.

Umbilical cord blood can be stored in two ways.

It can be stored in family banks or private banks or stored and donated into a public

bank for use by the entire population. Pathophysiology of Acute and Chronic GVHD.

And so this all leads into graft-versus-host disease.

And so what graft-versus-host disease is, is an immune reaction caused by the donor's

T-cells lack of recognition of the recipient's HLA antigens.

So the T-cells of the donor, seeing the tissue of the patient as foreign, and causing an

immune reaction.

This is the most common complication of allogeneic stem cell transplant.

With adult populations, it is almost a given.

It is reported to occur in 30% to 70% of all adult transplants.

Our pediatric numbers are smaller.

Including all comers transplanted at Children's Hospital and Dana-Farber, our most recent

incidence is acute GVHD of all stages and grades between 36% and 42%, with chronic GVHD

being around the same at 34% to 44% of patients.

So this slide shows the process or the pathophysiology of how we think acute graft-versus-host disease

occurs.

This is not the same process that occurs in chronic graft-versus-host disease.

And so, starting at the top, you have an insult to the tissue.

And so the lightning bolts represent chemotherapy or radiation.

What happens then as you proceed counter-clockwise is that the host antigen-presenting cells

get activated.

So these are the cells in the tissue of the skin, liver, immune system, lungs, other organs

of the person receiving the stem cells who get activated.

The host antigen-presenting cells, then present to T-cells that are coming from the donor.

And one of the jobs of the T-cells of the donor is to eliminate parts of the body perceived

as foreign, those T-cells from the donor, see the antigen-presenting cells in the target

cells of the host as foreign and cause an inflammatory cascade.

This then develops the Th1 cells which differentiate, and you see expansion of CD4 cells, CD8 cells,

and see increased cytotoxic killing, and a whole inflammatory milleux.

Now this process will go unabated unless immunosuppression is modulated.

The pathophysiology of chronic graft-versus-host disease is quite different.

In this case, what we see is expansion of the donor T-cells in response to the alloantigens

or the autoantigens that is not regulated by the normal thymic or peripheral deletion

that we see in healthy normal subjects.

The T-cells then attack the damage via two ways.

So one, in direct cytolytic or inflammatory attack, the inflammatory cytokines, which

then proceeds to fibrosis, B-cell activation which we don't typically see as part of the

pathophysiology of acute graft-versus-host disease, and the production of autoantibodies.

In general, we think of acute graft-versus-host disease as being inflammation and chronic

graft-versus-host disease as being more characterized by scarring and fibrosis.

GVHD Risk Factors and HLA Matching.

There are many risk factors for GVHD and the most important being HLA disparity.

So this is where we're talking about the matching.

And I'll talk about that briefly in a moment.

So the better matched you are, the much lower your risk of graft-versus-host disease.

Unrelated donors who have the equivalent matching of a matched sib still have a higher risk

of contributing to the development of graft-versus-host disease.

Older donor and older recipient-- so even within families, an older female donor is

more likely to contribute to graft-versus-host disease than a younger, equally-matched male

donor.

Sex mismatch-- and this is especially true of multiparous female women who donate into

male recipients.

The stem cell source-- so as I've mentioned, peripheral blood stem cells having a higher

risk of GVHD compared to bone marrow and umbilical cord.

The use of total body radiation in the conditioning regimen, the stem cell dose provided to the

patient, and noncompliance with graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis medications, and anything

that revs up your immune system, such as a viral infection or viral reactivation can

trigger the immune system to an uncontrolled point and lead to graft-versus-host disease.

So when talking about transplants, it's almost impossible not to talk a bit about the matching.

So this is the major histocompatibility complex genes that are found on Chromosome 6.

Those genes produce the 6 HLA proteins.

The HLA antigens are essentials of the activation of T-cells.

So on this picture, we see a cartoon of Chromosome 6 and the different pairs of chromosomes that

are important to the genes that are important to the development of graft-versus-host disease

and HLA matching.

And so we talk about matching on Cass 1 antigen, so A B and C, one from each parent.

So matching at A is matching at two out of six, matching and B is matching at two out

of six, as you have one chromosome from each parent.

Then the second, the Class 2 proteins are found on Chromosome 6 as well.

And those are DR, DQ, and DP.

Because HLA A, B, and DR are most associated with graft-versus-host disease, we count those

as a six out of six.

So matching at 2A, 2B, and 2DR beta 1 genes, would be considered a six out of six match.

When you add C, that becomes an eight out of eight match.

This is extraordinarily important.

And this is an old study, or old studies that demonstrate the importance of the matching.

So in the first column, we see the type of matching.

So antigen matching, which is done using antibodies, at a low-resolution level, in the first row

of the studies by Dr. Woolfrey, they had six antigen-matching, low-resolution, so antibody-only

matching.

And 64% of the patient matched at out of six places.

That, based on that low-resolution typing, had an 85% acute graft-versus-host disease

rate.

Now when we think about the higher grades of graft-versus-host disease, had almost 50%.

And this is a population that included children and adults.

What we then developed was high-resolution typing which is done at a PCR-based allelic

level.

When that typing is done, we have a better picture of the HLA typing.

And we see that, in the study by Dr. Rocha, that when low-resolution typing is done on

A and B, so matching at four out of six, and high resolution, or allelic-level PCR typing,

at DR, he found 80% of the donors used had this six out of six match.

And you see 56% of all GVH, and 30% of the higher grades, so indicating that better matching

results in less graft-versus-host disease.

And finally, in the most recent study looking at 10 allele testing, so adding more of the

genes that we talked about, all high-resolution typing.

Even with only 48% of those patients having a 10 out of 10 match, you see a much lower

rate of graft-versus-host disease, including 40% in acute, and only 8% in the grade III

through grade IV.

And so what that means is that we have learned how to type better at the PCR-based.

We are able to reduce the risk of graft-versus-host disease in patients, by choosing better donors

with a higher degree of match.

So the stem cell source as a risk factor we've already spoken about quite a bit.

Bone marrow is the standard.

So peripheral blood, and umbilical cord are compared to bone marrow.

Peripheral blood stem cells, to recap, have the highest risk of graft-versus-host disease.

This is primarily because they have the greatest T-cell load and are the most immunologically

mature of the stem cell sources.

This is balanced by the faster engraftment and potentially lower acute transplant-related

toxicities.

Umbilical cord blood has the lowest incidence of graft-versus-host disease due to the immunologic

naivete of the cells, you can tolerate a much greater mismatch of a donor.

So for a patient who we are unable to find a six out of six bone marrow donor, we can

use a four out of six cord blood donor with a similar risk of graft-versus-host disease.

The problem again, are the immunologic naivete, which translates into higher viral reactivation

rates and slower engraftment.

Just to sort of hammer that point home that mismatching is better tolerated with cord

blood than with marrow, we look at a study, again, from Dr. Rocha comparing sibling cord

blood use to bone marrow.

The top line shows the degree of full-matching in cord bloods.

So in this population, you see only 8% of those patients had six out of six match, compared

to almost 81% of the bone marrows.

And then when you look at a four out of six match, you see 41% of cord blood, whereas

only 0.4%, so less than 1%, of the marrows.

Despite the differences, and the seemingly better matching in the bone marrow group,

we see the incidence of acute-graft-versus host disease is lower across the board in

the cord blood, even though less well-matched.

But in this population, the statistical significance comes in with the chronic graft-versus-host

disease patients, where despite inferior matching in the cord blood, you have a 12% risk of

chronic graft-versus-host disease compared to 43% in bone marrow.

Definition of Acute Versus Chronic GVHD.

We've talked a bit about acute versus chronic graft-versus-host disease, and to dive into

that a little bit more, I just will talk about those definitions.

So historically, it was quite easy.

If you were diagnosed with graft-versus-host disease at less than day 100, you had acute

GVHD.

If you're diagnosed at greater than day 100, you had chronic.

The challenge is that this really doesn't address the range of GVHD presentation.

So if you had the same horrible rash at day 99 that you had a day 100, for day 99, you

would be called acute GVHD, and at day 100, you would be called chronic graft-versus-host

disease, knowing even that there was no real significant pathophysiologic difference.

This also didn't provide great prognostic data.

So acute graft-versus-host disease has a different prognosis compared to significant chronic

graft-versus-host disease.

So based on this, the National Institute of Health convened a consensus conference of

GVHD experts from across the country to look at those categories and to try and parse those

out a little bit to be more predictive or more indicative of the disease process.

So it has made things more complicated, but it also reflects their disease process more.

So we still have the two broad categories of acute and chronic GVHD.

Within acute GVHD though, we've now divided it into two diseases, as well as in chronic

graft-versus-host disease divided into two groups as well.

So classic acute GVHD is what most transplanters think of as acute GVHD.

So this happens less than or at day 100.

They have features of acute GVHD, and we'll talk about what that looks like and no features

of chronic graft-versus-host disease.

The classic, chronic GVHD is similar in its definition in that you have features of chronograph

graft-versus-host disease, but no features of acute GVHD.

The two more muddy categories are the persistent, recurrent, or late-onset GVHD in the acute

variety, where this happens after day 100, but has all of the features of acute GVHD.

So like I was saying, that same horrible rash or terrible bloody diarrhea that happens at

day 99, now if it happens at day 105, you're still called acute GVHD, assuming that there

are no features of chronic GVHD present.

And this also accounts for symptoms that start less than day when 100, get better, and then

recur after day 100.

In chronic GVHD, the overlap syndrome composes all of the rest of those patients.

So, no limit on time before day 100, after day 100.

And these cases, the features of acute GVHD are present, as are the features of chronic

graft-versus-host disease.

So within organ system involvement, there is some overlap.

So both acute and chronic, the most commonly involved system is the cutaneous system.

In acute, the next most commonly involved is the GI tract, followed by the liver, followed

by oral graft-versus-host disease and ocular.

There's a much more heterogeneous population or presentation in chronic GVHD, where skin

is followed by liver involvement, oral, ocular, GI, immune, followed by fasciitic muscular,

genitourinary, and pulmonary.

We think about the pulmonary system a lot, even though it is uncommon, due to the severity

of the presentation and the change in life expectancy of those patients.

There are features that are seen in both acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease within

the skin, erythema, a maculopapular rash, or puritis.

There aren't distinctive features within the skin, based on biopsy, that can distinguish

graft-versus-host disease from drug rash or other inflammation, which can make it challenging

to diagnose in this complicated population.

Within the mouth, both populations can have gingivitis, mucositis, erythema, or pain with

eating or drinking, especially spicy foods.

And within the liver, both acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease can be characterized

by an increase in the alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin.

Within a GI tract, it's very common to experience nausea, vomiting, anorexia, or diarrhea, and

failure to thrive.

Within the eyes, common features include photophobia, periorbital hyperpigmentation, and blepharitis.

Diagnostic and Distinctive Features of Chronic GVHD.

So to be called GVHD, you need to have diagnostic features.

You don't need to have all of the features listed on the screen, but you need to have

one of those to be considered chronic graft-versus-host disease in any of the areas.

And so for the skin, that includes poikiloderma, lichen planus, sclerosis-- so sclerosis that

actually mirrors scleroderma, autoimmune-type scleroderma or morphea.

Within the mouth, you can have lichenoid changes, hyperkeratotic plaques, so built up white

plaques of the mouth, and restricted mouth opening.

And the restriction of the mouth opening can occur, either due to the tightness of the

skin surrounding it-- so scleroderma has changes surrounding the oral opening, or actual fibrous

bands which develop inside the mouth of these patients.

In the genitourinary tract, you could see lichen planus changes, or vaginal scarring,

or vaginal stenosis.

We don't see this very frequently in pediatrics, and it's not clear whether it's not seen frequently

because it doesn't exist more commonly or because we don't do routine exams on our patients.

Within the GI tract, chronic graft-versus-host disease is relatively rare.

The most commonly seen thing is esophageal web strictures or stenosis or tightening over

the esophagus, which you end up getting symptoms of patients having dysphasia or food sticking

as they try to swallow.

Within the lungs, if you have bronchiolitis obliterans based on a biopsy, that is diagnostic

of graft-versus-host disease.

And within the muscle, fascia, and joints, this includes fasciitis and contractures.

It's interesting to note that there are no clear diagnostic features for the nail, hairs,

eyes, liver, hematopoietic or immune system.

These are systems commonly involved with graft-versus-host disease, especially chronic.

The distinctive features that you can use-- you can't make your diagnosis of chronic GVHD

based on this, but it makes you think about it-- are depigmentation of the skin, so areas

of hyperpigmentation juxtaposed with areas of lack of pigmentation.

And we've seen patients completely lose their melanin of their skin due to graft-versus-host

disease.

So impairment of the sweat can occur due to GVHD.

Within the nails, you can see dystrophy, so thickening or splitting of the nails.

You can see nail loss, actually children losing their fingernails or toenails due to GVHD

or pterygium unguis, which is overgrowth of the skin surrounding the nails.

Within the hair, children can develop alopecia.

This can be diffuse alopecia, this can be thinning alopecia, or even spotty areas of

it.

While this is not life threatening, it can be life altering.

It needs to be taken seriously in any patients, as once that alopecia happens and scarring

occurs, that hair never returns.

You can see thick scaling of the scalp or papulosquamous lesions covering the scalp,

or premature graying.

Within the mouth, chronic GVHD is often accompanied by xerostomia.

Mucoceles-- and I'll show a picture of mucocele in a moment.

Mucosal atrophy, pseudomembranes, ulcers-- other things to think about are the increased

risk of carries.

So graft-versus-host disease can cause scarring of your salivary glands and ducts since you're

without that saliva, and also difficulty sometimes with oral hygiene due to the pain that's associated

with brushing or other things.

Those patients are at increased risk for cavities.

The increased risk of other oral cancers-- depapillation, so loss of the tastebuds, so

difficulty actually tasting your food-- some increased sensitivities to food, so patients

often report things that are spicy or high in acid, tomato sauce, that type of thing.

Within the eyes, you see dry, gritty, painful eyes, conjunctive virus, sicca, diagnosed

with a Schirmer test, which we'll talk about, and punktate keratopathy.

It is important to ask children about these symptoms, as they very rarely volunteer dry

eyes as a symptom, especially the younger child.

The gold standard for diagnosis of ocular GVHD remains Schirmer's test, which evaluates

tear production.

In this case, what happens is that a small piece of filter paper is inserted into the

lower eyelid.

The patient is then given fleorescein eye drops to irritate the eye.

So what happens is that you watch how much-- from the irritation from the filter paper--

how many tears the patient is able to produce.

So it's a little bit old-school and slightly barbaric of a test, but what you end up doing

is measuring how far those fleorescein drops progress down the filter paper.

Anything less than 10 millimeters of the wetting is considered an abnormal test.

So that should be done in all patients with graft-versus-host disease, regardless of their

symptom screening, primarily because children, as I've mentioned, do not seem to report ocular

findings regularly.

The treatment can be either with artificial tears or immunosuppressive eye drops, so eye

drop containing either steroid or other immunosupression, such a cyclosporine.

There are surgical corrections.

You can actually ligate the lacrimal ducts.

So looking at the nasal lacrimal ducts, you can actually tie off the nasal lacrimal ducts.

You can ablate those, or what we will more commonly do, is actually put small plugs so

that any tears the patient makes can circulate over their eyes.

But it's not a permanent change those can be placed easily in the ophthalmologist's

office without sedation.

There are also the development of contact lenses that patients can wear that circulate

fluid and continue to moisten the eye throughout the day.

Within the genitourinary tract, you can see ulcers, fissures, and erosions.

Within the lungs, you can have bronchiolistis obliterans syndrome, which is diagnosed with

pulmonary function testing in radiology, but not supported by pathology, most typically

because the lung biopsy has not been performed.

Pulmonary graft-versus-host disease is very uncommon.

We think about it a lot as transplanters because it is associated with a significant mortality.

So the pathophysiologic features or the pathologic feature of pulmonary graft-versus-host disease

is bronchiolitis obliterans from a biopsy.

Shy of that, bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome is diagnosed with obstructive PFT changes

and the changes associated are found on a high-resolution CT associated with obstruction,

so mosaic air-trapping, bronchiolitis, and other findings is consistent with that on

a CT.

This is, as I've mentioned, a primarily obstructive disease.

Secondary to endothelial damage with resulting inflammation and scarring.

What we typically see on PFTs are a decreased FEV1 and a decreased FEV1 over FVC, so the

FEV1 to FVC ratio.

However, this can be complicated by a restrictive picture, either due to scelordermatous changes

or other restrictive things contributing, making it a bit of a mixed picture.

Pulmonary graft-versus-host disease is associated with a very poor prognosis.

So this is associated in children with a 40% to 50% mortality rate.

In adults, it is almost uniformly fatal.

The management involves treating with increased immunosuppression, and with severe disease,

patients have received lung transplants.

Within the muscles, fascia, and joints, you can commonly see a cramping of the muscles

or arthritis, myositis, or polymyositis.

Within the hematopoietic immune system, you can see thrombocytopenia, which is associated

with a very poor prognosis, eosinophilia, which we often think about as a marker of

GVHD, but is not a predictive one for many patients.

It is for others-- lymphopenia, hypo-- or hypergammaglobulinemia and the presentation

of autoantibodies.

In hepatic graft-versus-host disease, one of the other very commonly involved organs

is primarily cholestatic abnormalities.

Isolated transaminase elevation is uncommon.

Severe liver failure can occur due to GVHD, typically is a little easier to treat than

the other organs, but not uniformly.

The differential diagnosis includes infection-- viral or fungal, drugs, including the azoles,

Bactrim, and chemotherapy, so things that we use very commonly in stem cell transplant.

And iron overload, which due to inflammation in transfusions is also quite common following

stem cell transplant.

Then there was a mixed picture, which can be many other findings, which have been reported

with GVHD, but not enough to consider diagnostic.

So exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, pericardial pleural effusions, ascites, peripheral neuropathy,

nephrotic syndrome, myasthenia gravis, cardiac conduction abnormalities or cardiomyopathy.

Acute GVHD Grading and Staging.

So we talk a lot about grade IV, stage IV, these different things in GVHD.

And just to highlight the differences, staging is the individual organ systems.

The grading is the composite of all of those put together.

So a child who is having a large amount of diarrhea would be a stage II to IV, depending

on the volume, grade III graft-versus-host disease case.

Whereas someone with just a rash that covers less than 25% of their body's surface area

and no other findings would be stage I skin, which makes them grade I overall.

This is important, both for prognosis and also all studies of children with graft-versus-host

disease, so that we can learn from comparing similar populations across different centers.

Acute graft-versus-host disease is staged.

So it is staged based on the amount of skin surface involvement and the type of involvement.

So stage 0 is no evidence of graft-versus-host disease.

Stage I, in the two most commonly used scoring systems, the Glucksberg Scoring System and

the IBMTR, or the international Blood and Marrow Transplant Registry, involves less

than 25% of the body's surface area with any of the findings of GVHD.

This increases to stage IV, where you end up having a desquamation of bullae, in general,

and from the IBMTR staging, the bullae with generalized exfoliative dermatitis.

So these children, in the higher stages of graft-versus-host disease, can actually slough

their entire skin and look very similar to what you'd expect from a burn victim.

There are three staging systems available for GVHD of the gut.

That in green, is that which is used for pediatrics because it takes into account the patient's

weight.

The problem with the two other scoring systems is that they do not take into account the

patient's weight, and so a 16-year-old, for instance, with 500 CCs of diarrhea and a two-year-old

with 500 CCs of diarrhea would be staged the same, whereas we all know, intuitively and

clinically, that those are not the same things.

So what we use in pediatrics, is the Keystone staging, which basically is determined by

the amount of diarrhea per kilogram of the patient per day to stage.

As we go up in staging to stage IV, you see greater amount of diarrhea out during the

day.

The liver is the other organ that is staged to form your composite acute graft-versus-host

disease grading.

Again, there are two staging systems.

I think it's easiest to use the one which has units that your lab uses.

So we use the Glucksberg staging system at our center.

GVHD Prevention and Treatment.

So children with graft-versus-host disease, even independent of their immunosuppression,

are at risk for infection due to difficulty with either splenic function or their own

inherent immune system, which is compromised by GVHD.

So prophylaxis is necessary.

So pneumococcal prophylaxis, or asplenia prophylaxis, is considered the standard of care for all

children with chronic graft-versus-host disease, whether or not they actually have asplenia.

So this is thought to be due to a functional defect, rather than actual anatomic or physical

defect.

So the probability of sepsis in children with graft-versus-host disease at 10 years who

are not on prophylaxis is approximately 14%.

In children who have taken prophylaxis regularly there are no reports of fatalities, and that

risk of sepsis is almost nonexistent.

We continue at our institution, the standard, to continue for at least six months, following

the discontinuation of immunosuppression.

Fungal prophylaxis is necessary primarily due to the immunosuppression that's used,

so corticosteroid.

So we stop that, either when the patient is off steroids, or shortly after they have off

steroids and we expect the immune system to have recovered somewhat.

We do restart them if children have a flare of their GVHD and require treatment with greater

than 1 milligram per kilogram of steroid.

Pneumocystis prophylaxis is a standard for all immunocompromised patients in our world.

This includes six months of prophylaxis after the discontinuation of immunosuppression.

We prefer to use bactrim due to its better efficacy, but that may not be possible for

all patients due to counts or allergies, in which case, atovaquone and pentamindine are

acceptable alternatives.

Our local standard, although there is not agreement internationally or nationally on

viral prophylaxis, we tend to put patients on viral prophylaxis when they are receiving

greater than one milligram per kilogram per day of steroid.

So the prevention of graft-versus-host disease is important.

There is no recognized international or national standard.

There are many commonly-used regimens.

All the commonly-used regimens in children include, a calcineurin inhibitor, so either

cyclosporine or tacrolimus.

So commonly used regimens for an unrelated donor would include cyclosporine, methotrexate,

and corticosteroid, including rapamycin and tacrolimus or cellcept.

For siblings, there are no standards which use corticosteroid as prophylaxis, assuming

the sibling is matched.

Children have received cyclosporine with methotrexate, cyclosporine alone, or T-cell depletion, which

effectively removes the effector cells, the T-cells from the graft, in which case, you

need no supplementary graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis.

The challenge though, is that you have an increased risk of infection because you have

removed a important component of the graft.

The treatment, there is one area that transplanters agree, and that is a first line treatment

for chronic graft-versus-host disease or acute graft-versus-host disease and that is with

corticosteroid.

So no matter what the presentation, the first line treatment, either with or without other

agents or other therapies, is corticosteroid.

In most cases, the prophylaxis is continued in methylprednisolone, or depending on the

inpatient or outpatient, nature of the patient, prednisolone or prednisone is started.

There is a wide range of starting doses at anywhere from 1 to 20 milligrams per kilogram

per day of steroid.

There has been a randomized study comparing the use of high-dose, 10 milligrams per kilogram

per day, versus low-dose 2 milligrams per kilogram per day of steroid, and showed the

same response rate and the same survival rate at three years.

However, increased morbidity associate with a higher dose, so really showing no advantage

to using much higher doses of steroid for the majority of patients.

We typically, depending on the severity, will start at 1 milligram per kilogram of steroids

at our center.

If the child is already on steroids, that will frequently be increased to 2 milligrams

per kilogram of steroids.

We try to wean quickly, once the GVHD is under control.

There have been different studies of different tapering rates.

And the tapering rate considered fast, from a peak of steroids to off is 86 days, which

showed no difference from a 147-day taper, in regards to the flare or progression of

acute GVHD to chronic graft-versus-host disease.

Steroid Refractory GVHD.

Steroid refractory graft versus host disease is a real problem for our patient population.

So most patients, so over half, so 55% of patients improve with steroids alone.

35% of patients overall have a complete response.

However, there are certain population of children and adults who despite steroid treatment,

even high steroid treatment, progressed with their symptoms.

So the definition of steroid refractory graph versus host disease is progression of acute

graft versus host disease after three days of steroid therapy, or no clinical or biochemical

improvement after seven days, or an incomplete response after 14 days of therapy.

So with steroid refractory graphs versus host disease, we see a significant increase in

transplant related mortality.

So because of that, we often act very early.

So even after the progression after three days of steroid to add a second or third line

agent.

We don't necessarily recommend higher doses of steroids because all we have seen is incremental

risk of death, a 2% incremental risk of death for every one milligram per kilogram increase

in cumulative steroid exposure.

So by just increasing the dose of steroids, you're very unlikely to improve the treatment

of GVHD, but you are likely to increase the toxicity associated with graph versus host

disease.

There is no uniform standard for the treatment of steroid refractory graft versus host disease.

So based on that, you have a list of agents or treatments to choose.

I've just listed four of the common ones used on this slide.

So the first is pentostatin which is used for acute graft versus host disease.

The response rates anywhere from 30% to 90% depending on the organ system involved.

As you can see, pentostatin has poor success in the lungs.

And that will be the case for everything else on the list, the lung being very difficult

to treat.

The toxicities associated pentostatin include transaminitis, infection, and neutropenia.

And there are some practical issues.

So this is something that requires IV therapy in a clinic every two weeks.

So during the course of treatment, patients need to be seen every two weeks, receive their

IV, and then can go home.

Cellcept or mycophenolate mofetil.

It's taken orally.

This can be done at home.

It has best response with skin and liver, less good response with the GI tract, minimal

response with the lungs.

The common problems with Cellcept are colitis that can actually look under the microscope

very similar to acute graft versus host disease.

So we have to be very careful about that.

So diarrhea, infection, neutropenia, and nausea are most common.

Rituximab is interesting in that it doesn't target T-cells, which we've been talking about

as the leading cell the leading player in GVHD.

So rituximab targets the B-cells which are thought to affect the T-cell activation over

time.

And there are some patients, especially those who have disease that presents almost an autoimmune

type features, who do better with rituximab.

So rituximab is very good for the skin with an approximate 70% response rate, not great

for the lungs with the 5% to 10% response rate, and GI and liver being somewhere in

between.

The things that we like about rituximab is that it can be given infusionally, one infusion

once a week for four weeks, has a very long lasting effect, up to six months.

The challenge being that it decreases your B-cell function, almost ablates your B-cell

function, so children are still at risk for infection.

And finally photopheresis, which is extracoporeal photopheresis.

This is done commonly, has a pretty good response rate in almost all systems, and the best we've

seen for lung, though still not ideal.

There are some issues with hypotension, chills, some small decrease in your counts.

It tends to be less immunosuppressive than the other therapies.

The problem are the practical natures of it.

So you need to live near a center that can do ECP, or photopheresis.

There are limited centers for adults and even fewer centers for pediatrics.

Additionally, children need to be present in the clinic, initially, twice a week for

infusion lasting four to six hours.

And that occurs for 12 weeks.

And then if the patient responds, is spaced over time.

New and on the horizon are the use of monoclonal antibodies for graft versus host disease.

So I've listed infliximab, rituximab, daclizumab, alemtuzumab, and etanercept.

I've listed just a representative of each one drug to affect different systems.

So infliximab and etanercept affecting TNF and the TNF receptors.

Rituximab, which we just briefly talked, affecting CD-20.

Daclizumab affecting IL-2 and alemtuzumab affecting CD-52.

They affect the different cells.

They mediate very differently.

And all are associated with unique side effects.

This list is constantly changing.

Daclizumab is on its way out.

There are other treatments that are coming up.

And these are thought to be a safer, more effective ways and we can target specific

cells, rather than doing a larger whole body immunosuppression.

After that there are lots of other differences.

Just to show you sort of the list of things, in addition to what we've talked about that

people will talk about manifestations and how some of them respond better than others.

So on this organ manifestation of skin, liver, intestinal tract, you can see the therapies

that people think work better for those.

Though I will say, for all steroid refractory disease, the average is a 40% to 60% response

rate.

So we try our best to pick those that are more tailored to that organ, knowing that

it is imperfect.

And that we still may need to try a third line or fourth line agent.

GVHD Prognosis.

Acute graft-versus-host disease, what is the prognosis?

So this is old experience.

And we think we're doing a little bit better now.

As for the early days of transplant, the team at the University of Minnesota looked at 443

patients, so 245 of those patients, so 55% of the patients with acute GVHD had a durable

response rate.

53% percent were alive at one year and 42% went on to develop chronic graft-versus-host

disease.

It's important to notice that while 53% being alive at a year seems poor, the children and

adults in this study who underwent transplant, a large portion of them had high-risk malignancies

or leukemia, and very likely could have died of their disease as well as complications

of transplant.

So 53% in a population that includes adults is actually not too bad for transplant.

Patients with HLA mismatch unrelated donors are less likely than those with matched related

donors, or even matched unrelated donors, to respond to therapy.

So for grade III acute graft-versus-host disease, the overall survival in that category is 30%.

And in grade IV disease, the overall survival is as low, or has been reported as low as

5%.

And again, this is a primarily adult population.

Our outcome in pediatrics tends to be a bit better.

So for chronic graft-versus-host disease, the survival rates are equally humbling, with

a 10-year survival rate for patients with severe graft-versus-host disease, a 5% to

20%.

Poor prognostic features include platelets less than 100,000 at day 100 or the time of

chronic graft-versus-host disease development, and extensive skin involvement, and progressive-type

onset.

This is a challenging slide to end our talk on.

But I think it highlights that there is a lot of work to be done.

The onset of monoclonal antibodies has helped shift our treatment of graft-versus-host disease

over time.

And the keys are for us to identify it early so we can treat early and to screen for things

like pulmonary graft-versus-host disease, which have poor outcomes, in an attempt to

improve the overall survival and the quality of life of these patients.

Thank you, very much.

Please help us improve the content by providing us

with some feedback.

For more infomation >> How to use Instagram video 2017 - Duration: 4:33.

For more infomation >> How to use Instagram video 2017 - Duration: 4:33.

For more infomation >> Gaat JAIRZINHO voor TWEE VROUWEN tegelijk?! | Vluggertje #11 - Duration: 1:48.

For more infomation >> Gaat JAIRZINHO voor TWEE VROUWEN tegelijk?! | Vluggertje #11 - Duration: 1:48.

For more infomation >> "Questions The Bible Asks: What Is Truth?" - Rev. Vaughn Hoffman - Duration: 22:36.

For more infomation >> "Questions The Bible Asks: What Is Truth?" - Rev. Vaughn Hoffman - Duration: 22:36.

For more infomation >> Louisiana Sen. Conrad Appel talks budget, taxes, economy-Pt. 1 - Duration: 11:30.

For more infomation >> Louisiana Sen. Conrad Appel talks budget, taxes, economy-Pt. 1 - Duration: 11:30.

Không có nhận xét nào:

Đăng nhận xét