Good evening.

Good evening, and welcome

to the Marian Miner Cook Athenaeum.

My name is Wesley Whitaker,

and I'm one of your Ath Fellows this year.

It was 6:30 a.m. when David Guillen Acosta

stepped outside his house in Durham, North Carolina,

and headed to school.

The 19-year-old had just began his second semester

of senior year at Riverside High School,

where teachers considered him an exemplary student.

But that morning, Acosta never made it down the street,

as two immigration agents waited in the driveway

and commanded him to get in their vehicle.

A Honduran native who fled gang violence for the U.S.

at age 16, Acosta is among hundreds

of Central American youths around the nation

who have been targeted for deportation

on their way to class or to work.

Attendance dropped by one third in some of the classes

at Riverside High School in the days after Acosta's arrest,

and this is part of a concerning trend

of people in immigrant communities becoming isolated

from public resources that are crucial

to their safety and success,

including the silence of victims of domestic abuse

who fear contact with the police

will result in their information being shared

with Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

The Trump administration's approach to immigration

has brought the question of what it means

to belong in a community, political or otherwise,

to the fore.

Last night Nancy Pelosi spent eight hours

on the Senate floor sharing stories of Dreamers,

individuals who immigrated to America as a child

and were promised a path to citizenship

by the Obama administration.

Her message was clear; this is the only home they know.

Our guest tonight will draw

on the Declaration of Independence for guidance

as we struggle to answer these and other questions

surrounding citizenship and belonging.

Danielle Allen is a professor in the Government Department

at Harvard University

and at the Harvard Graduate School of Education,

as well as the Director of Harvard's

Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics.

She was appointed James Bryant Conant University Professor,

Harvard's highest faculty honor, in 2017.

Professor Allen is a political theorist,

who has published broadly in democratic theory,

political sociology, and the history of political thought,

and is widely known for her work on justice and citizenship

in both Ancient Athens and modern America.

Before joining Harvard she was the first

African American faculty member to be appointed Professor

at the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton.

Allen is a contributing columnist for The Washington Post,

and the author of six books,

two of which are on sale outside tonight,

including Our Declaration:

A Reading of the Declaration of Independence

in Defensive Equality, which won the Francis Parkman Prize

from The Society of American Historians,

and the Chicago Tribune's Heartland Prize for Nonfiction.

She also chairs The Mellon Foundation Board of Trustees,

is a past chair of the Pulitzer Prize Board,

and has served as the Trustee of both Amherst College

and Princeton University.

Professor Allen's Athenaeum presentation

is co-sponsored by The Gould Center for Humanistic Studies.

As always, I must remind you that audio and visual recording

are strictly prohibited, please silence and put away

your mobile devices at this time,

and please join me in welcoming

Professor Allen to the Athenaeum.

(audience applauding)

My thanks to Wesley, and thank you to Professor Faggen

for the invitation, and to the Fellows, Athenaeum Fellows,

for a lively dinner conversation.

As Wesley's opening remarks suggested,

the topic that garnered interest here

over dinner was immigration,

and so I will take up the challenge

and do my best, as a part of my remarks,

to explain how my time with the Declaration of Independence

has guided me in my own efforts

to think my way through the thorny questions

surrounding the immigration debate.

So I'll come back to that at the end of my remarks,

we'll work our way there.

And these are challenging times,

it can seem counterintuitive in a moment

where the media is in a constant frenzy,

accelerating our heartbeats with yet,

every 24 hours a new version of a crisis,

sorry, that we need to respond to,

it can seem strange to return to old things, old texts,

archaic, 18th century formulations, and so forth.

Yet as it happens, for pretty accidental reasons,

I've been living with the Declaration of Independence

for the last 17 years.

Never would've thought that I would spend 17 years

thinking about the Declaration of Independence,

and with every year it has become only a deeper

and richer guide for me.

So my purpose this evening is to invite you

into reflection with me about

the Declaration of Independence,

and the particular lessons it has for effective, equitable,

and even self-protective citizenship in challenging times,

that's my purpose this evening.

But it can be a guide, it can be a valuable guide,

only if it actually helps us with real questions

that we have now, so I'm grateful for the challenge

to take up the question of immigration,

and will do my best to share what the text has given me.

How is it that I ended up accidentally living

with the Declaration for this long?

When I was a professor at the University of Chicago

some time ago, I was lucky to be involved

in a humanities program for low-income adults.

Also one of your faculty members, Professor Bob von Hallberg

taught in the same program in Chicago,

and this was a course that sought to give people

who didn't sometimes even have high school degrees

the same quality of education that people sitting

in places like this get.

So they had literature, and history, and philosophy,

and art history, and as I wrestled with the question

of how to ensure that these students working two jobs,

or sometimes out of work, struggling with childcare

and city transportation, and so forth,

when I was trying to ensure that they could have

the same kind of education as my University of Chicago

students had, it was a hard problem to solve,

how do you do that?

And the answer I came to was, there would be no compromise

in terms of the quality of the material

that the students were introduced to,

the quality of the teaching experience,

but we would read short texts.

That was the solution, we would make things very short,

so I thought, what's the shortest, best text

I can think of?

And that was the Declaration of Independence.

1,337 words, you can use it to teach history,

you can use it to teach philosophy,

you can use it to teach writing.

What caught me by surprise

was that my students reacted to the Declaration

as an immediate source of inspiration for their own lives,

it was directly empowering.

And the teaching experiences I had in those night classes

on the South Side of Chicago were among the most moving

of my career, and the reason was because,

again, the students who would come to this class were there

because they were trying to change their lives.

They had been working too hard for too long

in ways that didn't feel like they were getting anywhere,

or their children were struggling,

or people that they loved had died of diabetes

and inadequate healthcare, or had died of gunshot wounds,

or were languishing in prison,

and they wanted things to be different.

At the end of the day, the Declaration of Independence

has at its core exactly that same urge, an assessment;

the course of human events is not going in a good direction,

I want a change.

That's it, that basic human purposive intention

to find a route to something better,

that's what structures the Declaration of Independence,

and that's what my students had,

and they gave me the empowerment of the text

by showing me how it resonated with them.

So I'm inviting you to join me tonight

in a similar period of reflection, because I think,

my belief is that the second sentence of the Declaration

provides the most efficient account

of the basic work of citizenship ever written.

Alright, so that's a big claim,

so I'll put it to one of you to find something

that does more, more efficiently than this.

So here's your test, you gotta beat this;

"We hold these truths to be self-evident,

"that all men are created equal,

"that they are endowed by their Creator

"with certain unalienable rights, that among these,"

among these, not a complete list,

"are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

"But to secure these rights, governments are instituted

"among men, driving their just powers

"from the consent of the governed,

"that whenever any form of government

"becomes destructive of these ends

"it is the right of the people to alter or to abolish it,

"and to institute new government,

"laying its foundation on such principle

"and organizing its power in such form

"as to them shall seem most likely

"to effect their safety and happiness."

Now, I know some of you have read my book,

so you already knew the sentence was that long,

but I'm guessing most of you didn't remember

that the sentence was that long.

We tend to think it stops after pursuit of happiness,

and there's a long and complicated reason for that

that I can get into if you're interested,

but the sentence, that's one sentence.

Five truths, we hold these truths to be self-evident,

people have rights, here's some examples,

governments are instituted to secure those rights,

and if the governments aren't doing their jobs,

they're not securing those rights,

it's the right of the people,

this is the most important part,

to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new government,

laying its foundation on principle and organizing its powers

in such form as to them shall see most likely,

probabilistic judgment,

to effect their safety and happiness.

Alright, so that last clause,

that's the one I want you think about and focus on,

lay the foundation on principle

and organize the powers of government,

that's a to-do list for citizenship.

You've got to understand the core principles

that you want to use to architect

your society's basic commitments, to build a picture

of where you're trying to go together,

and then you have to understand

the powers of government enough to figure out

how to build institutions to make those principles real.

We know they actually meant this as a to-do list

because when they gathered in June of 1776 in Philadelphia

for the first time to consider the question of independence,

they chose to set up several committees,

and I'll come back to these committees in a second,

but the reason they did this, they gathered,

and Richard Henry Lee proposed a resolution

that they should declare independence,

and they knew if they were going to take a step like that,

revolution, high bar for decision-making,

they wanted unanimity, unanimity,

and they knew in June they didn't have it.

So rather than calling the question, they said,

we're gonna procrastinate on this whole independence thing,

let's give it 'til July so we can see

if we can get ourselves unanimity,

but in the meanwhile, just in case we do decide

to vote for independence, here's what we have to do:

we need a committee that's gonna write a preamble

to go with this resolution,

that's the committee that starts drafting the Declaration,

we need a committee to write the Articles of Confederation,

and we need a committee to write treaties

with France and Spain.

So that committee drafting the preamble,

they had the job of laying the foundation

on some principles.

And the committees that were drafting the articles

and the treaties, they were organizing

the powers of government.

The Declaration was a to-do list, this is what you gotta do

if you wanna build a government or drive political change,

principles, organize the powers, two things.

It was enough of a to-do list

that when they came to the Constitutional Convention

they repeated for themselves this question

of principles and organizational form,

they actually debated at the convention

did they need a new statement of basic principles?

And they decided no, they didn't,

all they needed to do was rework

how they organized the powers of government,

hence the replacement of the Articles with the Constitution.

At the end of the day they weren't completely convinced

that their original of statement of principles held,

and so they had to have the Bill of Rights added on,

and they worked their way through that over time.

And of course our Supreme Court jurisprudence

is a history of this country's reconsidering

some of its basic principles,

rethinking how to articulate those.

But that's it, if you want just a one-clause description

of what a citizen has to do,

it's figure out the principles,

and understand the powers of government.

Now, what does it take to prepare yourself to do that?

That's why I'm glad to be invited

at the invitation of the Humanities Center,

you've gotta have philosophy, and religion,

and religious studies, and history, and political science,

and sociology, and literature, which teaches you

what happens when people act

on different kinds of commitments

and get into conflicts about them.

So you need the humanities and social sciences,

in other words, the only way to prepare yourself

for the work of basic citizenship

is with that set of disciplines.

But the lessons in that sentence don't end there,

it's not just that there's this to-do list,

figure out your principles, understand how to organize

the powers of government,

it actually gives us some thoughts about the principles too,

there are two really important ideas.

I already pointed to one of them,

this basic idea, people have rights,

and among these are life, liberty,

and the pursuit of happiness.

So those are examples, you gotta realize,

those are examples, which means right there they're saying

figure it out, people.

We've taken a stab, here's how far we've gotten,

what do you think, is healthcare of right, for example?

That's a question of principle

we are all currently debating.

It might help our healthcare debate a little bit

if we could realize that if we could separate the debate

into the question of principle,

is there a right to healthcare,

and then the question of organizational form.

Maybe you say yes, maybe you say no,

if you say yes you've got the Affordable Care Act

way of organizing stuff, you've got the Congress's

Better Way Plan possible way of organizing

the powers of government,

there are a variety of different ways

you could organize the powers of government

to deliver on a right to healthcare

if you decide that healthcare is a right.

Well, let's go ahead and separate those two parts

of the conversation, we might make some progress

if we could do that.

So that's the first additional lesson,

so when we think about principles they're reminding us

that they haven't finished the job,

it's for us to do too.

And so what is the job exactly, that they've given us,

or reminded us that we have?

We all have individual rights, we start there,

but the reason we've built all these institutions together

in the first place, is to secure those rights

and achieve our safety and happiness.

The sentence doesn't end on me, it ends on us.

So the challenge of the sentence is to learn

how to connect individual rights

and the pursuit of individual plans of action and purposes

to a shared common purpose, our safety and happiness.

Now, we all know that that's exceptionally hard to do,

so what does it have to say about how we do that?

To some extent the entire document is making the case

by example that you have to learn how to make your case

for why the position that you're taking is good for us,

is good for us, and you're gonna have to make that case,

you have to test that case out with people

who disagree with you.

So you better equip yourselves with the skills

of argument and persuasion.

Oh, that's the humanities again, right?

So this is why we need this kind of education.

So the Declaration then asks us

to recognize that our task requires diagnosing

whether our government is securing our rights,

"whenever any form of government becomes destructive

"of these ends, it's the right of the people

"to figure out how to build a foundation of principle

"organize the powers of government

"in such form as to us shall see most likely

"to effect our safety and happiness."

So that notion of what's most likely,

this is almost the most important point.

The best we can do is offer our best judgment,

without certainty, constantly working on that question

in conditions of uncertainty,

which means we've got to bring humility to the endeavor.

So alongside our capacity to talk about principles,

alongside our capacity to understand

how institutions get organized,

and how power gets structured through

institutional architecture, alongside that,

and alongside our persuasive ability

and our ability to think about rights,

and to connect my own story to our story,

we need to bring humility to the project.

Now, it's often the case that when I set out

to try to convince people that all you need

to think about citizenship and doing right

by your democratic responsibilities

is the second sentence of the Declaration of Independence,

the next thing people say to me is,

but what about that Thomas Jefferson?

Didn't he own slaves?

And what about that language, all men are created equal,

what about women?

So I want to address those issues,

because they are important,

and they often are obstacles to our ability

to take the lessons of this text seriously.

So let me start with the question of gender,

and then I'll return to the issue of race and slavery.

Abigail Adams was a remarkable person,

and her letters are as full of erudite political theory

and philosophy as any of the published essays

of the male Founding Fathers.

Her husband, John Adams, served on the committee

with Jefferson, in fact John Adams was the real

politico driving the work towards independence.

And the committee of five who drafted the Declaration

were Jefferson, Adams, Benjamin Franklin,

Roger Sherman of Connecticut,

and Robert Livingston of New York.

And Abigail had been urging John on

in the course of independence for some time.

She wrote to him in April after she'd learned

that it looked like things were moving forward,

and she was excited, she cheered them on,

she was glad to hear of the developments, she said.

But she also said, "And now that you're thinking

"about independence, and a new plan of laws,

"what about the ladies?

"What's the place of the ladies in your new arrangement?"

And she continued, "You men have had tyrannical power

"over women for centuries, and you've abused that.

"So are you going to take care of the women

"in your new arrangements?"

She said, "And if you don't, if you don't,

"we will foment for voice and representation,

"and we will foment a rebellion to achieve

"voice and representation."

So from the beginning Abigail was criticizing,

or raising the question of what was going on

with the place of women in the new political arrangements?

John got criticism from somebody else too

in a similar way about the issue of,

in the language of the time, Negroes and laborers,

somebody else wrote and said, well what about,

what's the place for Negroes and laborers

in the new arrangements that you're formulating?

And in both cases John wrote back something similar.

What he wrote back was, "The principles,"

life, liberty, and happiness,

the notion that we're pursuing people's wellbeing,

"that applies to everybody.

"But the powers of government,

"the way in which we're gonna organize

"the powers of government, is in a patriarchal form."

Men, white men with property, have the job

of operating power in order to deliver on those rights

for everybody, those goods for everybody.

And Abigail was not convinced, Abigail said,

"Well," again, "we'll let you try one more time,

"but if you don't succeed, we will foment rebellion."

And sure enough that's what happened,

we got the Suffrage Movement and so forth,

but the point of saying that is,

that the distinction between the principles of government

and how we organize the powers of government

helps see why we can take from our founding,

even at the same time as we modify our institutions.

The principles were meant in a universal way,

the language of men was meant as a universalizing term,

and we know that because in the draft of the Declaration

Jefferson referred to men who are bought

and sold at auction, and that was a category

that included women, it included children,

it included African Americans obviously,

'cause that's who he was talking about.

So the principles did mean to convey something universal,

but the powers of government, the Founders,

were committed to patriarchal forms of organization,

and so we've been working since that time

to reconsider how we organize the powers of government

to set them in relationship to our principles.

Now what about the issues of slavery and race?

There's a lot to be said here as well,

and again, the same point I just made pertains,

so in the draft of the Declaration Jefferson described

the people of Africa, distant Africans,

as having sacred rights of life and liberty

that King George had violated by protecting the slave trade.

So the principles, again, apply even to Africans,

but the powers of government, different question.

But the more important thing to say about race and slavery

in the Declaration is this; there are two compromises

in the Declaration.

We understand the Constitution to have compromises,

we don't often see the compromises in the Declaration,

but there are two.

There's a good compromise and a bad compromise.

The good compromise is a compromise around religion,

there is no language about religion in the Declaration

that connects the Declaration to a specific

religious tradition, it's all open-ended;

Divine Providence, Supreme Judge, Creator,

never connected to a single tradition.

What's more, the language for religion was connected

to a language for natural science,

they talked about the laws of nature and nature's God,

so even people who were deists and shading into atheists,

could sign onto the Declaration.

All the different flavors of religious view

in the colonies were encapsulated

in the capacious open-ended language

of the Declaration for religion.

Now, the slavery compromise has been harder to see,

and it came in this way; there is a passage in the draft

that condemns King George for the slave trade,

I just alluded to it, and that got cut out by Congress,

that got cut out by Congress,

that was a pro-slavery moment in the drafting

of the Declaration.

The anti-slavery moment comes in right in the beginning,

that list of rights, life, liberty,

and the pursuit of happiness.

It wasn't life, liberty, and...

Property. Property, yeah.

And why not?

Because in the Fall of 1775 the royal governor of Virginia,

Lord Dunmore, had decreed that any slave

who ran away from the British and fought,

or ran away from a plantation and fought for the British

would be free.

This radicalized the Virginians,

it is what committed them to the cause of revolution,

so we all have to acknowledge that a defense of slavery

was a part of what drove the Revolutionary War.

At the same time that it committed the Virginians

to the war, it meant that they started complaining

about King George for having violated

their rights of property.

So from the Fall of 1775 a defense of the right to property

became entangled with the defense of slavery.

Alongside that argument, John Adams from Massachusetts,

who never owned slaves and thought slavery was a bad thing,

was trying to articulate a different view

of how to describe the purposes of government.

"Happiness," he said, "was the end of government,

"just as it was the end of individual men."

And over the course of the Spring he was arguing

over and over and over again that happiness

was the term they should use to define the core principles

they were seeking to protect.

And we see the compromise starting to take shape

when in Virginia, in early May the Virginians draft

their own declaration of rights, and George Mason

writes out, life, liberty, acquiring and securing property,

and pursuing happiness.

He puts both the Southern property concept

and the Northern happiness concept

in the Virginian text.

And then by July with the Declaration

property is squeezed out, we get happiness,

the position of those who don't want

an endorsement of slavery in the Declaration,

so that's the anti-slavery moment in the Declaration.

And we know it was that, we know it was that,

because the first people, the very first people

to make use of the Declaration for political purposes,

other than the Revolution itself, were abolitionists,

and they used the second sentence.

So Prince Hall, a free African American in Boston,

in 1777, January of '77, submitted a petition

to the Massachusetts Assembly for emancipation.

And by 1780 emancipation had been achieved

in Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, and Vermont;

the Declaration coalesced the Abolitionist Movement.

So our early history has multiple

political traditions in it,

not just the tradition of Jefferson the slave owner,

not just the tradition of white supremacy,

the tradition of abolitionism goes right back

to the beginning as well,

and the slavery compromise in the Declaration,

compromise though it was,

provided a foundation for the Abolitionist Movement,

it's important to recognize that feature of the text.

But this then brings me to what I take

to be one of the Declaration's most important lessons,

and one that has been, for me, the hardest to come by.

Democracies depend on compromise,

because without it they'll just break.

At the end of the day, those who are in the minority

on a given position have to be able to go along

with those in the majority, and if at the end of the day

you can't find your way to compromise,

is livable, capacious solutions,

then those who lose out have no reason

to stay in the game, at all.

So without compromise, democracy's not a viable

political form, yet we're not very good

at compromising these days,

it's become a weakness in our political practice.

Why are we so bad at compromise?

There are a lot of reasons, but I actually think

that the slavery compromise is one of the reasons.

None of us want to do that,

none of us wanna make that kind of mistake,

compromise on a matter of core principle

in a way that puts us on the wrong side of history,

which means we have to ask this really hard question,

how do you tell the difference between good compromises

and bad compromises?

And can the Declaration help us to draw a distinction there?

So that's where I come back again then

to these two compromises, religion compromise,

and the slavery compromise.

I called the first a good compromise,

I call the second a bad compromise,

what makes the difference between them?

Well, the religious compromise, in fact,

took into consideration all of the different

religious positions and experiences

then in existence in the colonies,

that is, all affected by the decision

and choices of formulations

were part of the deliberative process

achieving the compromise.

Now, let's consider the slavery compromise.

Were all affected included?

Exactly, no, I don't think it would've come out as it did

if all affected had been included in the decision-making.

Which means, as we're thinking about

the foundation of principle we want for our society,

we may have just discovered another one;

that the way you could have compromise

and avoid bad compromises is if you recognize inclusion,

full inclusion of those affected

by the decision-making process, as fundamental

to achieving a just outcome.

Hmm, okay, interesting.

This is where then, I get to thinking about

our contemporary circumstances and the issue of immigration.

We've got 11 million undocumented people in this country,

our politicians are hard at work, well maybe,

(audience chuckling)

trying to come up with a solution to this problem.

Have we actually figured out how to include,

in the right ways, the voices and perspectives

of those who'd be affected by our decision?

Or are we in danger of making a decision or a compromise

like the slavery compromise?

11 million people have been working very hard

in this country, not all of them I admit,

yes, there are people who do bad things,

though we all know that the crime rates of immigrants

are lower than crime rates of native-born Americans,

so there's a whole lot of fire, and noise, and smoke

being blown around about issues in inaccurate ways.

11 million people, most of whom working incredibly hard,

who've brought a lot to this country,

where there are confusing distinctions

between the category of refugee and immigrant,

some people who are under an immigration category

look like they're fleeing pretty desperate circumstances,

particularly in Central America, which are,

dare I say, of our making, of our making.

If we stop to think about what the war on drugs has done

to the legal regimes of Central and South America,

it gets awfully tangled up.

But, so for my own personal effort to think my way through

the immigration question, I have come to believe

that in order to address it fully,

we have to figure out how to include

the perspectives of the 11 million undocumented individuals

in our conversations.

Now, you're bound to ask me exactly how to do that,

and I don't have the answer, but that's why I came to CMC,

where all these brilliant young people studying

and working hard on these questions.

So I think the charge I'm putting to you

is how do we even begin to design public conversations,

public decision-making processes, that ensure

that those affected by the decisions that we're making

have voices that are heard as part of our process.

We do know how to include the voices

of people who don't have formal citizenship,

because we do it for children all the time.

I'm not drawing an analogy between children and immigrants,

except for in a formal way,

that is that the legal status is related.

And we would never think it appropriate

to disregard entirely the experience of children,

nor would we think it appropriate to empower them,

strictly speaking, as voters on a given decision,

but we find a way, nonetheless, of ensuring

that their voices are part of the process.

And so I think that's the hard question we have to work on,

as we struggle our way to understanding both

what's the foundation of principle

that we want to build on to shape

the direction of our country,

and how do we organize the powers of government,

including achieving voice and representation,

Abigail Adams' words, words she used at a point

when women were not part of the political system,

nonetheless she wanted voice and representation,

how do we achieve that in our organizational forms now

with regard to the issue of immigration?

Thank you.

(audience applauding)

Thank you very much Professor,

we will now be opening it up to questions.

If you have a question please raise your hand

and either Wesley or I will come and hand you the mic.

Okay.

So thanks, I'd like to say that I particularly

appreciated that because it's not often that I find myself

encouraged by, or attracted to, more optimistic takes

on, I guess things in politics generally,

so I really appreciate this.

And related to that, I'm wondering what you might say to,

specifically thinking about in the second sentence

where it says that the people have the right to either

adapt, change, alter, thank you, alter, or abolish

the present form of government, what do you say to people

who think that it's already a time to abolish,

or perhaps when do we know it's just time to abolish

rather than to alter?

I'd love to hear either of your thoughts on those.

So the very next sentence of the Declaration

says that government should never be changed

for light and transient causes.

In other words, they move directly from

the right of revolution that they've just articulated

to an account of the standard you have to meet

in order to trigger the abolish prevision,

as opposed to the altering one.

And so what does it mean to sort through

whether or not causes are light and transient?

For them what it meant was they could point to a record

of 10 years of concerted effort in petitioning the king,

laying out alternative policy proposals, and so forth,

and it was because they had been consistently working

and gotten no response, no movement whatsoever,

that they decided that they had reached that point.

So that was the justification that they offered.

In our own circumstances, there are all kinds

of different issues people are working hard on

and concerned about.

The ones that I know the most about,

things like criminal justice reform, for example,

healthcare, among others, in each case,

if you take criminal justice reform

that's an area where most of the work that needs to be done

is on the state level, not the federal level.

The majority of the operations

of our criminal justice system are organized by state law,

and few people participate in state politics these days.

So there has not been a concerted effort

to redirect our state laws.

So that's just one area of policy,

but that's how you think about it,

you have to figure out what are the actual avenues of change

and has a fully concerted effort on all dimensions been made

over an extended stretch of time that one could point to

as a historical record in order to justify a decision

of a certain kind.

But just to say, at the same time,

you've put your finger on one of the paradoxes

of the American founding, which is that

it's insane to aspire to build a new and durable government

on a principle of revolution,

a sort of paradox built into the heart of the thing.

But that, then again, is why practices of citizenship

are so important, and understanding effective citizenship.

I think that there is huge amounts of room for alteration

inside our current institutions,

and that's what I'm trying to help people see.

Hi.

Thank you so much for coming,

I wanted to ask about your definition

of good versus bad compromise,

you argue that a good compromise is one

which included the perspectives of all those

relevant at the time, or present at the time,

I wanted to ask can we apply it to queer rights,

the identity of gayness of course didn't exist at the time,

and so some perhaps, necessarily gay perspectives

clauses were included because the definition don't exist.

We existed, but our identity did not exist,

so how then would you go,

or would you have to, a project of constructing gay rights

off of the Declaration, or would you see it

as having to be added separately?

Thank you.

Thanks, I think I would say something similar

to what I said about gender and race,

that the phrase all men was intended in a universalizing way

that the errors that they made came in,

and how they thought about how to organize

the powers of government, and so I see our responsibility

as being a matter of understanding how to structure

the powers of government to make good on the idea

that all people have rights,

and those rights need to be secured by their government,

and that it's our job to give those rights definition.

Life, liberty, and pursuit of happiness is a starting point

for that conversation.

Over the course of the 20th century

the right to association was added,

so for example, we put a lot of emphasis now

on the right to association as a core right,

that right wasn't formulated

until Supreme Court jurisprudence

in the middle of the 20th century,

which people don't often realize.

And then on that right of association we've built

a right to marriage, marriage is a form of association.

So that's an example of how,

in our Supreme Court jurisprudence,

we've been extending the conversation about basic principles

over time under the penumbra of our rights discourse.

Hi, thank you so much

for your talk.

I was particularly struck as well by your distinction

between good and bad compromises, and I was curious,

we've seen so many compromises being made

in Washington right now, both good and bad.

Do you think there's maybe some mechanism

we can put in place to better encourage good compromise

while discouraging bad compromise?

Yes!

(audience laughing)

And it's called the Fair Representation Act,

which has put forward by a member of Congress from Virginia,

and what it proposes is to convert to

an electoral structure for Congress

that consists of multi-member districts

and rank-order voting.

And what this would result in is that the majority

of Congressional districts in the country

would be represented by both a Democrat and a Republican,

or they would have a group of representatives

who would represent both parties.

Because the way rank-order voting works is

if your first choice doesn't make it past the post

your vote goes down to your next choice, and so forth,

and if you've got multi-members then you'll end up with

some members representing the majority,

and some representing the minority.

That would mean that any given Congressional district

would be represented by people from differing,

people from different parties

would have the same constituency,

and they'd have to figure out, together,

how to serve their constituency.

So I think that the work of compromise

is partly a matter of the ethics we bring to politics,

but it's also a matter of our institutional structures

and the kinds of incentives that are designed into them,

and I do think that we need to redesign our institutions

to some degree.

The proposal that I've just mentioned isn't radical,

so how Congressional elections are handled

is controlled by Congress,

it's not even a matter of Constitutional,

it doesn't rise to the level of the Constitution,

and these modes of voting have been used in the U.S.

at different points in time

in different parts of the country.

So it's well within the realm of the imaginable,

doable political reform.

Thanks for speaking with us.

When most of us think about the Declaration of Independence,

I think we make an assumption that it's a document about,

here are all the tyrannical things that the state

may not do, but you expressed how, especially for Adams,

the motivation of the political philosophy was the idea

that the government can actively promote happiness,

and that state action might advance the national interest

in beneficial ways.

So for you, is the Declaration of Independence

a fundamentally deontological document about natural rights,

or is it a consequentialist document

about advancing utility, or somewhere in between?

Oh, I love that, thank you, alrighty.

See I told you, I was coming to CMC to get a place

where I'd get hard questions and good answers

on the hard questions that I'm also posing to you.

So I would say it's neither,

so I think it's a pragmatist document

in the sense of the American philosophical tradition

of pragmatism, also politically pragmatic,

but the pragmatism matters, and let me explain

how that works.

That sentence is really incredibly important,

and it's one that has predecessors

in the previous 15 years of American politics.

Actually John Adams wrote a version of that sentence

in January in a proclamation he wrote for Massachusetts,

and John Wilson 10 years earlier had written

a version of the sentence, so they've been noodling

on the question of how to define this thing they're doing,

and it's finally, it crystallizes finally

in Jefferson's formulation, but it's been coming together.

And the key part of it is, there's two parts that are key;

one, simply the recognition that human beings are purposive,

that we pursue happiness, that every day we're trying

to make today better than yesterday.

It's very basic, we all have this,

it's a thing that makes us equal,

it is the feature of our equality.

And that human history has shown

that we've been building these institutions,

governments to help us do that,

but the second important part,

so A, human beings are purposive, B,

it's the right of the people to figure out

how to secure their safety and happiness.

Now, there's a really important idea buried in that

that's hard to get to, it gets more fully articulated

by Mill later, but the idea is that

only the people for themselves can judge

whether things are going well for them or not,

for each of us individually, and for the people together.

By that I mean, although each of us makes

all kinds of bad decisions, and we all know people

who make a lot of bad decisions consistently,

it is still true that each of us has better access

to what's good for us, what we're trying to be,

what our purposes are, than any other human being

could possibly have.

So there is no other person who could do

a better job for us than we have the potential

to do for ourselves and setting our own direction,

that's the key insight, the end of that sentence.

You put those things together, human purposiveness,

and the fact that each of us is best positioned

to be the judge of our own purposes,

and you get the core elements of pragmatism.

So we're seeking something that we'll loosely call happiness

and then we have to judge repeatedly

whether we've gotten it, but all we can do

is make a prediction about what's most likely

to get it for us, which means we also

always have to be prepared to correct ourselves.

So there's a certain kind of, what people call fallibilism

and corrigiblism, built into that.

So that's it, a loose conception of human flourishing,

that's what keeps it from being deontological,

it's too open-ended, and then it's about our judgment

in relationship to our flourishing,

and that is what keeps it from being utilitarian,

because it's not just a straight mathematical principle

about a kind of aggregate good,

it's what each of us individually has to judge.

And over time as we correct, and so forth, we improve,

and so that bundle of things with the fallibilism

and corrigiblism is what gives you the package

that people call pragmatism, alrighty?

Thank you very much for your talk,

I thoroughly enjoyed it.

You talked a lot about the second sentence

in the Declaration, and that sentence

talks a lot about rights, of which are life, liberty,

and the pursuit of happiness,

and the right to displace the government

if it is not fulfilling its obligations.

But implicit at the end is, I guess and obligation

to ascertain or reflect on what is most likely

to bring people safety and happiness,

and the safety and happiness of your fellow citizens.

Nowadays in a lotta countries you see that people

are forced into those obligations,

in Singapore, in Israel, in South Korea people are forced

to consider the safety of their fellow citizens

and are obliged to some form of national service

or something of that sort,

and in other developed democracies you, I feel,

see, correct me if I'm wrong, but a loss in

a recognition that we have an obligation

to our fellow citizens.

How do you cultivate feelings of obligations

to fellow citizens in order to cultivate

a more civic community?

I'm gonna answer the question by turning it upside down,

if you'll permit me.

You asked the great question of how do you cultivate

a sense of obligation to fellow citizens,

by turning it upside down I mean you could ask the question,

how do we avoid cultivating

a sense of enmity amongst ourselves?

Now, when I turn the question upside down like that

I'm actually asking James Madison's question about faction.

So we talk a lot about polarization these days,

and partisanship, we could call it faction.

Now, the reason it's worth turning the question around

that way is because at the founding they put

an awful lot of thought into the problem of faction

and how to dissolve it or mitigate it.

And it's important to think back to their answers

because they don't work anymore,

and I wanna be very clear about why they don't work,

because then you'll get the answer to the question

you started with.

If you go back to Federalist 10,

that's the important instance of the Federalist Papers

where Madison takes up the question of

how in this big, diverse country where you're gonna have

all these different kinds of interests and point of view,

the whole thing won't just disintegrate

into dangerous factionalism or minority factions

that can tyrannize the majority, and things like that.

And there are two parts to his answer,

people tend to focus on the part

that is about representative institutions,

the argument is that you'll have these representatives

who are elected from the different parts of the country,

and they'll filter opinions and give us

a more moderate set of opinions for actual decision-making,

that's part of the answer.

People miss that the other part of his answer

is that the actual geographic dispersal of the country

will contribute to resolving the problem of faction.

So the way the argument goes is that

people will be so spread out and hindered by mountains,

and rivers, and things like that, that it'll be very hard

for people with extreme views to combine with each other.

And when you put that fact together with

the representative system, so then you have,

it's hard for people with extreme views

to actually find each other and combine,

and so the extreme views really do get filtered

through representatives who have a moderating impact

who can then bring together a national conversation.

You can see where I'm going with these points, right?

The geographic premise of the design doesn't hold,

it's gone.

So that's why it's not working, people.

If we wanna fix it, we actually have to revisit

the basic questions of institutional design,

that's why I raised the Fair Representation Act

as one possible alternative approach

to institutional design.

There are others, I'm actually a supporter

of national service, for a related reason.

Complicated, volunteering alongside military service,

et cetera, you still get some self-selection,

anyway, I'm a supporter of geographic lotteries

for college admission.

(audience chuckling)

Anyway.

I like to put these things out there

because the point is that there are,

we can redesign our institutions,

and we actually need to redesign them

because again, that original premise doesn't hold,

but the point is that then if you can redesign

the institution, and so the incentive is to compromise

and cooperation, you'll start to get a culture

that is about remembering, again, learning again

what are obligations are to one another.

So we get back to that culture

by undoing the problem of faction

through institutional design, that's the argument.

Hello, I had a question on

is visibility a requirement for democracy?

In the case of undocumented immigrants I find that

visibility and representation can often be coercive

and even unethical, as the state apparatus brutalizes

immigrants for their visibility.

We can see this particularly in the case

of migrant rights activists getting targeted

for being public about their status,

among many other examples,

so is visibility as a method towards inclusion for you

a concept that is absolutely necessary for democracy?

In that case I would think that detention

and deportation policies would have to be

extensively reworked so that people actually feel safe

to be visible, or can undocumented immigrants

practice inclusion or engaging any social citizenship

within democracy without visibility?

Thank you, that's a good question.

At the end of the day, voice and representation

require visibility of some kind,

but I think that there are different ways

of approaching that in different contexts,

and I think there is room

for voice and representation by proxy.

I think you're asking, your challenges of,

there are two different kinds,

so there's the issue of undocumented workers

or members of our society who are at great risk

if they expose themselves, there's a separate issue

of people with permanent status,

whether a citizen or otherwise, who are allies

and working on behalf of immigrants rights issues,

and who are nonetheless harassed or made vulnerable.

I think in the latter case it's incumbent

on a bigger group of citizens to be working

on behalf of strong legal protections for activists

working in that space.

So that's one issue, and I think that one is,

one can think about within the parameters

of our existing ways of thinking about issues of protest

and activism, and things like that.

The Dreamers case is a particularly interesting one,

as I'm sure you know, because the very fact that

there was protection of any kind achieved

did depend on the amazing bravery of a campaign

of young Dreamers, who define themselves that way,

imagine a campaign of coming out videos, and so forth.

And if you look at the kind of policy

record at the state levels, it's a complicated story,

so you see a combination of both great gains,

but also really strong backlash.

So you can tell I don't have an answer to your question,

I'm just sort of thinking out loud with you.

There's no question about the dangers involved in this,

but from my point of view what those dangers really do

is point to the problem of statelessness,

which is a problem that Hannah Arendt wrote about

a long time ago, what it means for people to be stateless

is to be thoroughly exposed and no protections

of the most basic human rights.

And so from my point of view, the conversations that we have

in this space should begin with the notion

that every human being has a right to be a citizen

in some state, and that no citizen, no person should exposed

to statelessness.

Now, for me to say that doesn't get us very far,

'cause I'm one person,

and that doesn't yield much protection,

but that's the kind of case I think we should be making

in order to secure some basic human rights protections.

Hey, thank you for coming.

I'm interested in the Fair Representation Act

and the idea of multi-member districts,

I think it would be more fair in general,

but it also would probably give more power

to people who are now Democratic party,

and so people who are now Republicans might seek to undo it.

Would you hope that that kind of a compromise

would just work out so well

that everyone would be happy in the end,

or how would you think that that kind of thing

can be sustained, 'cause there's been reactions

in our history to those kinds of changes.

So it's interesting, I don't think I had that take

on it's favoring Democrats ultimately,

there are all kinds of places where it would give

Republicans more of a voice than they currently have,

so in most Blue states it would increase

the influence of Republicans, for example,

and conversely in Red states.

We probably have a different empirical sense

of what would happen, so given that let's talk afterwards,

you should share with me where you get your line from

and I'll see what I can figure out.

Thank you for being here tonight.

In your chat you talked about that the nature of citizenship

as the nation was being forged

and a national identity was being found.

And at a time when people, I think, are rightly cognizant

and wary of terms like nationalism,

how do you deal with the relationship

between national identity and citizenship?

Oh gosh, that's an interesting question.

Would it be fair to say your question

is also a question about patriotism?

I think so. Yeah, alrighty.

Well now I'm just trying to understand the question.

It's funny, I don't know why,

I don't think about it that way, so let's see.

Yeah, I dunno, that's so funny.

I guess I don't think about it that way because

the relevant terms of membership that I'm focused on

and am articulating have to do

with a set of ideals and institutions.

So that is connected to a specific tradition,

of a specific place, specific country,

the United States of America and so forth,

and so the argument that I'm making is one for pride,

and that history and those traditions,

and I think, I guess the reason I don't,

yeah, I tend to use the word nationalist

but I don't tend to connect it to,

my line of thought has to do with the different

kinds of meanings and traditions

behind the concept of nationalism.

What I'm trying to say exactly I suppose is just that

at the end of the day, I focus on the concept of the people,

and a people bound by a set of commitments,

and therefore with a kind of open-endedness

to who could participate in that,

and it's in the cultural fabric.

So insofar as nation concepts have tended to connect to

cultural communities, I tend to think of that

as a different conversation, to be honest.

That probably sounds very strange,

but that's the case, that is, yeah, that's the case.

So for me patriotism is about these ideals,

these institutions, and the strength and prosperity

of a political community glued together by them.

Sorry, I know I've missed the force of the question,

but that's, nobody's done that to me in a long time.

(audience chuckling)

I think I agree with you

more-- No, no, no,

can you say a little bit more,

do you mind saying a bit more about your question,

I'm sorry, I just wanna understand a little bit better

what you think the stakes are

of putting those things in relationship to each other.

I think nationalism is a really

kind of charged term that a lot of people are afraid of,

but I think there is an idea there

that I think you got at that's really important,

kind of a buy-in to shared values

and some sort of identity,

and the fear comes when it's cultural

or when it's associated with a specific group of people,

I think that kind of sense of nationalism

has really been used in a bad way throughout history,

but to me there's a value there, I think you pointed out,

with the term patriotism,

that I think I might be considering

the plus side of nationalism that I would consider

vital and necessary if you're gonna have

the kind of citizenship you're talking about.

Okay, so that's it, so thank you, that was very helpful.

So I think that's exactly what's going on,

is that the concept of nationalism

doesn't in itself convey anything

about ideals and institutions.

And as such, I think it actually

doesn't help us understand our own traditions,

I think that's what I'm getting out.

Hello.

Thank you so much for coming,

I'm actually one of Professor Strong's serious students

at Panola College, so I've got both of your books,

'cause-- I think yes,

and we've met before,

haven't we? Yeah, we met before.

Alrighty, nice to see you.

Good seeing you again.

So my question's actually more about the international law,

international human rights question,

which is not really the master focus right here,

but I was wondering, so there's constantly talks

on how there's a proliferation of rights,

of human rights, on this international scale,

and what do you see that the U.S. Declaration,

and framing process, and the document itself,

how does it help, say, guide our thinking

in international human rights,

and that proliferation that we're talking about here?

I mean, the history of rights is fascinating,

and there's been a lot of change since the U.S. Declaration

up to the U.N. Declaration of Human Rights, and so forth,

and even from the U.S. Declaration

to the French Declaration of Rights of Man and Citizen

there's already a change.

The U.S. Declaration of Independence really focuses

on the concept, for example, of political equality,

and the political rights that are attached to that.

The French Declaration begins to introduce

a concept of economic rights,

by the time we get up to the U.N. Declaration

we've got cultural rights, social rights of education,

health, and so forth, alongside political rights.

And I think the result of that is

we have a different kind of intellectual challenge now

than 200 years ago.

One way I like to put the nature of the challenge is,

if I invoke the concept of equality

you shouldn't let me stop there,

you should ask the question of what kind of equality

I'm talking about.

Am I talking about human moral equality,

am I talking about political equality,

am I talking about social equality,

am I talking about economic issues,

certain kind of economic egalitarianism,

talking about gender equality, or racial equality,

or many different kinds of things I might be talking about.

And in order to think about the ways

in which bundles of rights interact with each other,

I think we have to think about

how those different kinds of equality

interact with each other.

It's my own view that, in our policy-making landscape

for the last 50 years, political equality has fallen

too far down the list of important kinds of equality,

and that consequently our political rights

have fallen too far down the list

of what we should be paying attention to.

So in my book, and in my arguments generally,

part of what you're getting is an argument for rebalancing,

in favor of political equality, and political rights,

in relationship to other categories of rights.

Amartya Sen is a philosopher and economist

whose work I much admire, and I follow his line of argument

that in some sense political freedom is fundamental

to achieving a bundle of goods

that support human capacities.

So to argue for rebalancing in favor of political rights

and political equality, it's not to put issues

of material wellbeing off the table altogether,

but it is to make the argument that we get to

shared prosperity through free political institutions

and political freedom.

Hi again. Hello.

So I've been having a difficult time

trying to figure out how to articulate the question,

and I think it might be because

part of the problem might be that it's actually

outside the scope of what you're talking about,

but I'm thinking about

the notion-- I noticed that stopped

your colleagues.

(all laughing)

Fair enough,

then I'll feel comfortable.

So I'm thinking about the notion of good compromise

as being compromises which include in the discussion

all of the people who are affected by the decision,

but then having that in mind alongside concerns

and considerations about polarization

and a lack of, as was mentioned,

the sense of obligation to our citizenry,

and it makes me wonder about the kinds of things,

irrespective of the quality of the compromise

with respect to inclusiveness and involvement

in the decision-making, the kinds of things

which ought not to be compromised on,

if those things exist.

If so, how do we go about still talking about them,

and then if not, how do we go about convincing ourselves

and each other that there's nothing we can't compromise on?

I'm gonna separate the question into two different parts,

your second question, is there anything

we can't compromise on implicitly,

and a question about how we actually work through

the very hard conversations that are about issues

that at some level we start by thinking

we can't compromise on.

So yeah, so I think there are things

that we can't compromise on,

so I won't enumerate those now,

but I do take the basic principles of equality

to be a starting point for understanding

where those things are.

To say that there's a distinct difference

between good and bad compromises

doesn't mean that there aren't limits

to the zone for compromising, there have to be limits,

there have to be places where you decide

it's time to fight, that's just human life

teaches that lesson.

But in terms of, I mean I think,

what I'm hearing in your question,

so you should tell me if I'm getting you wrong,

what I'm hearing in your question

is partly a question about hard conversations

on college campuses.

No? Oh, alright,

okay, well then I don't, what I was hearing was

the challenge of, for example, our debates about free speech

and academic freedom, and things like that,

and those points where one side thinks

the other side is making an argument

that should be one that we don't compromise on,

it shouldn't even be articulated,

that was the kind of issue I was hearing.

Yeah, I think that actually didn't,

oh it's back on, thank you.

I think you're right to say that that's related,

it just wasn't want I had in mind

'cause I'm exhausted of that conversation.

Got it. But, I mean stretching it

off of college campuses I guess,

similarly conversations with colleagues, family members,

people in the same political sphere,

just about how we vote, or what we think, et cetera.

So I see, okay, so it's a big field.

Okay, nonetheless I'm gonna try to speak

to the college campus piece of it

on the idea that things we might say about that

can also be extended to other contexts, alrighty?

So the thing that's distinctive about the college campus

is that doing the work that we do here

depends on academic freedom.

So that's a bit different from marriage, or friendship,

et cetera, the kinds of relationships

where you don't say absolutely everything you think

because you'd ruin it.

But college campuses depend on academic freedom,

and that means being on a college campus

is partly about figuring out how to live

through really hard, bad arguments,

but I think we also, one of the goals

of developing cultures where compromise is possible

is about recognizing a responsibility to prove

oneself trustworthy to the other members of one's community.

And the need to prove oneself trustworthy

begins to set the parameters on how one pays,

how one thinks about what one's going to say,

and that doesn't set parameters on one's views,

but it means that it sets parameters on how

one goes about thinking about articulating one's views.

So then I think that leads to needing to recognize

distinctions among the kinds of ways

in which speech can do harm

or show that you're not trustworthy.

There are the easy cases of slander,

and libel, and defamation,

and threat, and slurs, and harassment,

we actually have huge numbers of legal categories

for dealing with those things, those are easy.

And then there are two hard categories,

there's the accidentally insulting category,

which just doesn't do anybody any good

to cause accidental insult or to be accidentally insulted,

and that's a place where I think we just,

as a part of proving ourselves trustworthy to each other,

have a responsibility to show each other

where those places are so that well-intentioned people

can avoid them.

And that doesn't mean you need elaborate policies,

it just means you need a culture

of expecting to prove yourself trustworthy

and being willing to hear, oh that was insulting,

oh, I didn't intend it, okay on we go,

we've clarified there's a little accidental insult

happening in that space, we can do better than that.

The hardest part is the part where you've got arguments

or views that some group or party will consider

existentially threatening.

So the immigration debate is a good example there,

so there are various positions, exceptional positions

on our political spectrum that are existentially threatening

to some members of a college community.

So how do we approach articulating views

when they're existentially threatening to other people?

Another example would be my book

on the Declaration of Independence,

I am very critical of Libertarianism

in a way that you could consider it being a straw man

representation of Libertarianism,

and as the author of the book I have to recognize

that a Libertarian might consider my book

existentially threatening.

So what's my responsibility in relationship to that,

how do I prove myself trustworthy?

I have to convey my commitment

to that person's wellbeing in the community,

this is on a college campus.

Then it's a question of how one approaches

articulating one's views,

and I think this applies across the political spectrum,

but I do think a basic part of meeting one's obligations

as a member of a community is about proving

oneself trustworthy to others,

and therefore requires one to work through

the question of how to convey

existentially threatening views

in ways that nonetheless prove your trustworthiness.

Yeah, you don't buy it.

I don't think it's that I don't buy it,

it's just that that's a really tall order.

That's true.

Yeah, I don't know.

That's true, it is a tall order,

but I think for me that's what we're here for

on college campuses, is this is the place

where we have the opportunity, the space,

the privilege of trying to make the most of ourselves,

including in this zone of figuring out

those points where we feel like

we're in existential conflict with each other,

and figuring out how to live through them,

move through them to another place.

Thank you so much

for coming to speak with us,

it's been one of my favorite talks

that I've ever been to, so thank you.

Oh my.

(audience chuckling)

I just wanted to push back

on one of the responses you gave earlier to a question,

which is that each individual is most able to identify

their own interests, and I would agree with you

in terms of when those principles that we all share

are being violated, but then I'm quite pessimistic

about the ability of each person to determine

which policy apparatus or set of institutions

can then best address their grievances,

I think the recent election is a great evidence of that.

So in Gov 20 where we read your book,

but we also read Tocqueville,

he addresses this distinction by saying

that it's better to have a well-intentioned

but untrained politician advocate for these interests

as opposed to a malintentioned but well-trained politician.

How do you address that nuance and trade off?

That's a great question, thank you.

There are two different, let me see,

there are three different judgements at stake here.

There is a judgment of an individual

about his or her own course of life,

there's a judgment of each individual

about the collective course,

and then there are the judgments made

through our political institutions by representatives.

The judgements of individuals about our collective course

and representative democracy typically get exercised

through the selection of representatives,

so at the end of the day we end up

having to make proxy decisions

for a set of potential policy views.

Now, the important point is that

the judgment of individuals and the people

is the ground in those first two cases,

and then the third type of judgment,

the judgements made through our political institutions,

are what I would call an epistemic problem,

that is, it's a question of how you combine

the different kinds of knowledge and insight

in a community into a shared judgment.

And there I would agree with you,

I think yes, it's a matter of combining expertise

with the knowledge of lay individuals

about how a given policy plays out in their community.

The view that I've articulated about individual's

special position in relationship to their own wellbeing

results in a view about political decision-making,

where you would never toss it over to the experts alone,

but that you're always building your institutions

in order to integrate expert knowledge

built up in particular policy arenas

with the judgments people are making about core values,

broad directions, that they wanna set for society.

Unfortunately that is all the time we have

this evening, please remember that we are selling

Our Declaration outside, and please join me

in one more time thanking Professor Allen.

Thank you.

(audience applauding)

For more infomation >> NYC Prepared For Mother Nature's Wrath - Duration: 2:15.

For more infomation >> NYC Prepared For Mother Nature's Wrath - Duration: 2:15.  For more infomation >> Reba McEntire's former Tennessee home now available for parties, events - Duration: 2:16.

For more infomation >> Reba McEntire's former Tennessee home now available for parties, events - Duration: 2:16.  For more infomation >> Gov. Malloy proposes fairness bill for female prison inmates - Duration: 0:38.

For more infomation >> Gov. Malloy proposes fairness bill for female prison inmates - Duration: 0:38.  For more infomation >> South Shore Gearing Up For Another POwerful Storm - Duration: 2:43.

For more infomation >> South Shore Gearing Up For Another POwerful Storm - Duration: 2:43.  For more infomation >> "We're Heartbroken For Both Of The Families" - Duration: 1:57.

For more infomation >> "We're Heartbroken For Both Of The Families" - Duration: 1:57.

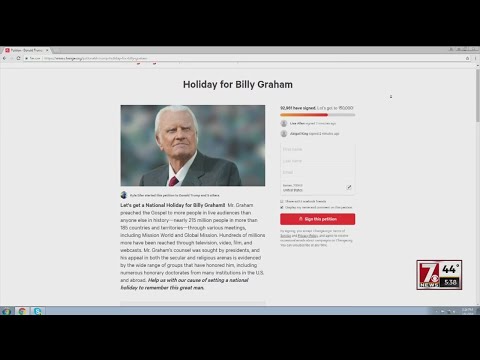

For more infomation >> Petition for Reverend Billy Graham Holiday - Duration: 2:32.

For more infomation >> Petition for Reverend Billy Graham Holiday - Duration: 2:32.

For more infomation >> Experts Warn of Growing Trade for Jaguar Parts in China - Duration: 0:53.

For more infomation >> Experts Warn of Growing Trade for Jaguar Parts in China - Duration: 0:53.  For more infomation >> Long Island Getting Ready For Another Nor'easter - Duration: 2:22.

For more infomation >> Long Island Getting Ready For Another Nor'easter - Duration: 2:22.  For more infomation >> Bright's Zoo open for business after massive fire - Duration: 1:03.

For more infomation >> Bright's Zoo open for business after massive fire - Duration: 1:03.  For more infomation >> Coastal communities brace for another round of storms - Duration: 2:54.

For more infomation >> Coastal communities brace for another round of storms - Duration: 2:54.  For more infomation >> Evans High School students to hold local "March for Our Lives." - Duration: 2:27.

For more infomation >> Evans High School students to hold local "March for Our Lives." - Duration: 2:27.

Không có nhận xét nào:

Đăng nhận xét