(audience applauding)

- Thank you all for being here.

It's just so exciting to see such a huge crowd,

and it's really evidence to us that there's a real appetite

for thoughtful and spirited conversation

about the public good, about the common good,

so we're just thrilled that you're here.

I'm Dr. Erika Kidd.

I'm with the Catholic Studies Project

here at the University of St. Thomas.

Let's welcome the president of the University of St. Thomas,

Dr. Julie Sullivan.

(audience applauds)

- The Murphy Institute is a strategic venture

of the College of Arts and Sciences Center

for Catholic Studies and the School of Law.

It works to engage our community in rigorous discussions

that bring Catholic perspectives to bear

on law and public policy debates.

In a world that often seems polarized,

we know that we must resist categorizing those

with opposing views or beliefs from our own

as evil, or stupid, or ignorant.

In fact, they may know and understand things that we do not.

And it is only when we start with this assumption

that no one has negative intent,

and everyone understands things and some things

that we do not

that rational discourse can begin.

And we know that worthy debate and challenge

are central to the pursuit of truth.

So we are very excited to be

hosting this conversation tonight.

Mr. Douthat and Dr. West are certainly worthy challengers.

And certainly neither considers the other as evil or stupid.

And I look forward to their

conversation this evening. (audience laughs)

About Christianity and politics in the U.S.

Thank you for being with us.

(audience applauds)

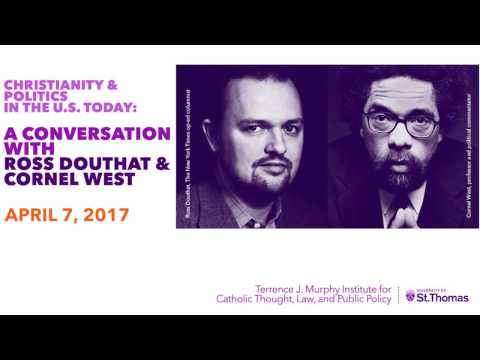

- We at the Murphy Institute have been toying

with the idea of inviting these two guests

for quite a while, but it was aligned from one of

Mr. Douthat's New York City Times column

that spurred us into action.

Weighing the possibilities for a revitalized religious left,

he wrote, "I would far rather debate politics

"with Cornel West or the editors of Commonweal

"then with the liberalism that thinks it can impose

"meaning on a cosmos who's sound and fury

"signifies nothing on its own."

And we decided that would be a conversation worth watching.

(audience and Dr. West laugh)

- I appreciate that.

(audience and Dr. West laugh)

- Be careful what you wish for.

(Dr. West laughs)

- The conversation will be moderated this evening

by professor of law and co-director

of the Murphy Institute, Lisa Schultz.

- So, let's begin.

This is gonna be fun, right?

Let's start with a question ripped from today's headlines,

President Trump described yesterday's U.S. missile attack

on the Shayrat airbase in Syria

as furthering a vital national security interest

of the United States to prevent and deter the spread

and use of deadly chemical weapons.

He called for all civilized nations to join us

in seeking to end the slaughter and bloodshed in Syria

and also to end terrorism of all kinds and types.

And he said "we hope that as long as

America stands for justice,

then peace and harmony will in the end prevail."

This action is consistent with this country's highly

interventionist model of foreign policy,

going back to the great World Wars.

As a consequence of this policies,

the U.S. spends a truly phenomenal amount of money

on military and intelligence.

My question for each of you

is whether and how the teachings of Christianity

should inform American Christians' political stands

toward military interventionism.

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and Dorothy Day

both argued that the teachings of Christianity

were incompatible with these state of affairs.

Others such as Richard John Neuhaus and George Weigel

have consistently defended U.S. military actions

by appeal to the doctrine of just war.

What do you make of the division among American Christians

on this issue?

Is there any hope of building something like a consensus

among them?

And if so, what might it look like?

I think, in general, if you look at the nature

of American military interventions,

especially I'd say in the post Cold War era,

when we passed out of the period where we were

going as far as we did propping up dictatorial regimes

in Latin America because of the Soviet threat and so on.

When you pass out of that era,

if you're just looking at the level of sort of ideals,

what are you trying to accomplish,

you can very often make a case, as in this case,

that there's a perfectly reasonable case

based on sort of cosmic justice for the idea

that we are intervening to attack a dictatorial regime

that's slaughtering its own citizens and so on.

And the moral case is there and real.

At the same time, part of I think just war theory

properly understood is that you have to also

take into account issues like the likelihood

of your action leading to a truly good outcome

further down the road.

And so, I guess this is a way for me to try and slip

myself in between Dorothy Day's pacifism

and my friend George Weigel's take on the Iraq war.

It's also a limited strike that is designed essentially

to attempt to punish Assad for a specific crime.

And you could make a sort of narrower argument that

if you're not planning to escalate,

that kind of proportional response

falls within just war theory, even if you don't

have a brilliant plan for the day after

and the day after that.

So I guess I would say I'm more inclined to endorse

a limited strike than a more open-ended intervention.

But I don't have great confidence that either

suggests a clear path towards the kind of

ultimately positive outcome that would make this fit

neatly under just war theory.

How's that for a (audience laughs)

tap dance, tap dance through the issue.

- I'll say this though,

that I like what brother Trump said that he acknowledged

that the killing of the precious children moved him.

Because that's a starting point for me.

You see, I'm a Christian, I look at the world

through the lens of the cross.

I begin with the vulnerable, and those who are crust

and those who are often overlooked.

And a child in Syria, a child in Minneapolis,

a child in Tel Aviv, a child in Hebron,

a child in South Side Chicago all has the same value for me.

It's how I look at the world.

The legacy of Dorothy Day, which is towering.

The legacy of Martin Luther King is towering,

but I'm not a pacifist, I'm a Christian but not a pacifist.

I agree with my dear brother Ross here in terms

of trying to take seriously

the tradition of just war that goes all the back

to the great Augustine himself.

And the question then becomes, well, let's look at the data.

United States dropped thousands and thousands of bombs

on Syria last year.

Obama dropped 26,192 bombs,

six countries in 2016.

So it's not as if this is a shift.

(audience members laugh)

It's deep continuity in U.S. foreign policy

in dropping bombs with very little public accountability,

high quality public deliberation about it

with precious children being killed too.

See, so that's just a context (audience applauds)

you want to keep in mind, you see.

Now, because I have so little confidence in vision,

character, intellect, dot dot dot,

of brother Trump, (audience laughs)

brother Ross is right.

How does this fit within a certain direction?

Where it is going?

We always want to opt for diplomatic

ways of dealing with these kinds of conflicts first,

no doubt.

And there has to be moments in which just war is important.

We were right to fight against the Nazis, and so forth.

I think Nelson Mandela was right

to found the spear of the nation against the Apartheid

state of South Africa after over 60 years

of non-violent resistance and getting crushed

like cockroaches.

He disagreed with Martin King on that.

Christians must learn how to disagree

because we're finite, we're fallen, and so forth.

That's part of what constitutes the tradition, you see.

Now, in this particular moment,

I do think that we have to have some way

of bringing these crimes against humanity

on a variety of sides in Syria,

and we have to understand what led toward

the situation in Syria.

When I hear arguments about,

well, he's doing certain things to his own citizens.

Well, I heard that in Libya.

You didn't hear that in Chile.

When Pinochet was doing things to his own citizens.

Oh, no, silent then.

But I get a little suspicious in terms of

what rationalizations are.

- On one thing that's interesting,

you know, I'm a political journalist.

I write in a context where most of my peers

are not prophetic philosophers,

but Washington insiders. (Dr. West and audience laugh)

And it is striking how there's a weird sense

of almost relief among a certain kind

of political journalist that Trump,

brother Trump, President Trump, brother Donald,

by the end I'll be in the flow.

(audience laughs)

That he did this

because it's such a

normal presidential thing to do.

And it's normal for the reasons that you suggested,

because the last president dropped a lot of bombs,

and the president before that dropped a lot of bombs.

And it's been part of our, in effect,

management of the world order for a long time.

But it's also normal in a way that sort of goes,

it's more normal than Obama.

Because Obama was distinguished by his refusal

to do exactly this the last time Assad

crossed the line and sort of used chemical weapons

in a way that nobody could deny.

And Obama took the view basically that there was

what he and his people would call this foreign policy blob,

which was not a term of endearment,

that dominated thinking in Washington

that the blob's perspective was always

that, you know, there's always gotta be a military response.

There's always gotta be a military solution.

And Obama saw himself as resisting all of that.

And I know you feel that he did not

resist it quite sufficiently.

- Over 500 drone strikes.

That doesn't strike me as constraint, but go right ahead.

- Can I suggest a little bit of a thought experiment?

Suppose that the attack of president Assad

had been revealed to the world

and the use of sarin gas had been revealed to the world,

and brother Trump's response had been to do nothing,

how would each of you evaluate that response?

- It would depend on what kind of argument

or narrative he put forward as to why he did nothing.

There's a wonderful essay by H. Richard Niebuhr

called "The Grace of Doing Nothing".

Sometimes grace goes along with doing nothing.

Sometimes cowardice goes along with doing nothing.

Sometimes ignorance goes along with doing nothing.

Sometimes wisdom goes along with doing nothing.

We'd have to look and see how,

now, of course, we don't expect that much

out of the brother, but (audience laughs)

this is a real thought experiment,

you know what I mean? (audience laughs)

We assume Trump just graduated from the University

of St. Thomas, took his philosophy course,

his theology, studied Aquinas and Augustine

and then moved up Jeff Stout and some other

contemporary theorists.

But we'd have to flesh out what kind of narrative

he and his group, because really it's not just him.

Brother and I were talking in the green room,

he's got a little group around him.

And I asked brother Ross, I said

who in the White House comes close

to having integrity, or at least a semblance of integrity?

- And I said Sean Spicer.

(Dr. West and audience laugh)

- And the second part of the answer was,

the military. - The military, right.

- And there's something about the formation

in a martial temperament that's different than commerce

and commodification.

I remember when I spoke at West Point,

one of the things we shared in common is

I'm a warrior, I'm a love warrior.

I come out of the legacy of Martin Luther King, Jr.,

and John Coltrane and Fannie Lou Hamer, Ella Baker.

You see, and they are warriors for the nation.

I got the cross, they got the flag.

But we're warriors.

There's something about character formation

in being on a battle field

of life and death.

And so, in that sense, I wasn't surprised

when you actually bring in these military folk,

and I'm very suspicious of empire.

I'm anti-imperialist.

I want to proceed very close or carefully

in terms of valorizing the martial spirit

too much in various forms.

But at least there's a commonality here.

Because once commodification sets in,

it's all theater, it's all titillation,

it's all stimulation,

and it's 11th Commandment,

"Thou shall not get caught winning at any cost

"for the spectacle."

You see, that's called spiritual blackout

from my tradition, 'cause spiritual blackout

is the relative eclipse of integrity, honesty,

and decency in doing anything to win

and simply posing and posturing

like a peacock, but so much of American culture

is opposing and posturing of peacocks.

That's all you need to do. (audience applauds)

Just stay on the surface, you see.

And so, I appreciated that answer because

we understand why the military in this sense

within that circle would surface

with some gravitas.

- Well, and it seems like my impression

of the president is that there are two groups of people

say mostly men, two groups of men that he respects.

And one group are the people who are

at the apogee of that commercial culture

and that you just lambasted.

And the other group are the men who are at the apogee

of the military.

And that's why his cabinet is,

you know, it has some professional politicians in it,

but what is distinctive about it compared

to every cabinet in my lifetime

is that it's a mix of CEOs and generals.

- Over the past few years, the Black Lives Matters

movement-- - God bless them.

God bless them. - --has drawn attention

to the structural injustice suffered by racial minorities

groups in the United States, particularly African Americans.

And indeed, Professor West, your arrest in Ferguson

in August of 2015 is a testament to your concern

for that continued structural inequality

in the United States.

The involvement of faith communities in the civil rights

movement in the 1960s was very significant

in galvanizing the support of the entire country

for the legal reforms that eventually were implemented.

What is or should be the role of Christians

in Christian faith communities in forging a similar consensus

for this contemporary assault

on these structural injustices?

- Yeah, I just think to be a Christian is to

choose a way of the cross that has to do

with unarmed truth, and condition of truth is always

to allow suffering to speak and unconditional love.

And when Martin said justice is what love looks like

in public, he wasn't saying that love

and justice are identical, but they are indivisible.

And the great Niebuhr used to say,

any justice that's only justice soon

degenerates into something less than justice.

Justice is rescued only by something deeper, which is love,

so this dialect go in between love and justice?

But it's a matter of Christian witness.

And what was wonderful about Ferguson the second time,

not the first time, the first time it was

the young people themselves.

It was Tef Poe in the others all by themselves.

But the second time you got a wave of ministers,

stayed cool,

Jim Wallace,

Tracy, a whole wave of ministers.

Now, I'm a minister, I'm a lay Christian.

That's a sign of divine wisdom.

I never called to be a minister.

(audience laughs)

But it was a wonderful thing

to have some fellow Christians there.

We had Jewish brothers and sisters there,

the legacies of Rabbi Abraham, Joshua Heschel, and others.

We had the rabbis there.

We had the Islamic ministers there.

We had Buddhist temples,

I mean, Buddhist leaders and so on.

So there was a wonderful religious witness there.

But I think the important thing about it is not to

either fetishize.

You don't want to describe magical powers to it

and so forth.

Or you don't want to completely ignore it

because our secular brothers and sisters, you know,

usually when they invoke Christians,

it's the Christian right.

And I say, well, I have a tradition I can introduce you to.

(audience laughs)

Fredrick Douglas to Martin King to Fannie Lou Hamer,

to Dorothy Day and Philip Berrigan.

It goes on and on, that's a prophetic Christian tradition.

It's always been leaven in the loaf,

it's always been relatively weak and feeble.

The way it across is always weak and feeble

because the dominant ways of the world

are envy and resentment and domination and subordination

and hatred and revenge.

It's always been that way.

Will always be.

Will always be.

The question is, how strong is the counterforce

and the counter voices?

In any particularly generation.

And that's why Ferguson was so important.

That marvelous new militancy,

but the challenge, of course, is that will it be

a moral and spiritual awakening so that they'll choose

love and justice, rather than hatred and revenge?

- What's your prediction?

- Open question.

- Well, let me ask you a question.

- Mm-hmm.

- So, it seems to me as

from the political right, someone who's sort of an observer

of these traditions but has theological common ground

with them, that there is a big difference

between where the civil rights movement was

sort of theologically and religiously

and where, taken as a whole, Black Lives Matters has been.

And I think it says something about

not just sort of left-wing protest movements themselves,

but whats happened in American culture

over last 50 or 60 years.

Which is that institutional churches generally

have gotten weaker. - That's right.

- The sort of religious center has fragmented.

That the civil rights movement happened at a moment

when you could get,

suddenly, you could get Catholic archbishops

and black ministers sort of on the same page,

when you could,

you know, Billy Graham was no hero

of the civil rights movement, but he didn't fight it.

He integrated his rallies and so on.

And today we're in a different landscape.

In some ways we're in a more secularized landscape.

We're in a landscape that's more fragmented,

more people who identify as religious

but don't go to church.

But when I look at our politics right now,

and this is true on the right too,

I look at sort of where left-wing protest movements are,

and then I look where the alt right is

and some of Trump's more, shall we say,

racially aware supporters.

And I see the intimations of a kind

of post-Christian politics, where you're getting

into a landscape where the left has gone

from we're the religious left to we're the spiritual

but not religious left to sort of we're just the left.

And where the right is sort of rediscovering

the awful power of sort of, you know,

its own kind of racial identity politics.

And I wonder what you,

I wonder if you worry about that happening.

I worry about it on my side.

A lot of conservatives, a lot of religious conservatives,

we didn't expect Donald Trump in part because

we thought the religious element in American conservatism

was stronger than it was.

And I wonder what you see when you look at the left

and where it is today.

- Well, I'll say this, my dear brother,

I was not surprised about how weak the religious dimension

of my fellow right-wing brothers and sisters

within the Christian tradition

that for so often, they acted as if they had

these deep convictions, and then here comes Donald Trump

and they adjust so quickly.

And you say, oh, (audience applauds)

I see, I see.

How deeply committed you really were here.

Mmm, mmm, mmm.

- Harsh, but fair.

(audience and Lisa laugh)

- You say it in love, you say it in love.

But some folk you gotta love at a distance too, though.

You know it's true.

Same kind of folks that'll shoot you down, you know.

But the point is you'd laid bare a very

rich narrative over the last 50 years,

I mean, let's just remind ourselves,

49 years ago and three days brother Martin

was shot down like a dog in Memphis.

That's the B.C., A.D. moment

in the history of American democracy.

If we were to go back to that moment,

what would we find in Minneapolis?

Probably was on fire.

Had 150 cities on fire.

First time the National Guard had to protect the White House

since the civil war.

The white power structure opened itself.

And it was not the legislation.

It was the massive rebellions with our precious brother

who loved us so shot down in that way.

As Christian, as black, as human, as Jim Crow,

a child of Jim Crow, and so forth, you see.

But he represented, like a John Coltrane in music,

a level of spiritual maturity and integrity.

I didn't say purity. He was flawed. He made mistakes,

private life, public life.

But he had a spiritual integrity,

and he had a maturity.

We've lost so much of that,

no matter what color we are.

I am very old school in terms of

these older legacies that come out of Athens and Jerusalem.

That come out of Egypt and Paris and Harlem,

and so forth, you see.

- But you want it all to hold together.

Right, you want John Dewey in there.

And I think John Dewey's your enemy.

- Oh, no, no. - No, I think

the drift of university, - He's my comrade.

- No the drift of university education in this country

took us away from Athens and Jerusalem

starting in the late 19th century.

It didn't happen with,

I mean, it happened with commodification

and commercial later on, but it started with the idea

that we're sort of molding this sort of secular citizen

who, and this isn't particularly Dewey's fault necessarily

'cause it predates him, but it starts with the idea

that the university is a place

where it's about technical mastery,

and it's technical mastery that's

deeply connected to the kind of capitalist culture

that you decry.

And this is a thick strand in progressivism,

which is intention with parts of the Christian left,

but it's one of the reasons why liberalism

has ended up in this distinctly secular place, I think.

- Well, let me ask you one question

before I really go at you here, brother.

- Yeah, yeah. (audience laughs)

- Would you include the inimitable Ralph Waldo Emerson?

- In, I mean, I would say--

- As the proto figure headed toward Dewey.

You don't see Emerson tied to the legacy of Athens

and Jerusalem?

- No, Emerson is.

- Oh, but see Dewey comes out of Emerson.

- Okay, but it's the same issue I was talking about

where everything is connected to everything else,

right?

That's the nature of human life in human history.

But as you move along the chain,

you can reach a point where you've still turned

into something different.

And I think that's my problem,

if I have a problem with parts of where the left

has ended up.

That if I go back to the civil rights movement

and I listen to the civil rights movement,

I hear something who's politics aren't exactly

the same as mine sometimes, but we're still speaking

the language of Christianity together.

And when I listen to parts of,

I mean, it's not specific to Black Lives Matters.

Black Lives Matters probably has more theology in it

just by virtue of having some connection

to the black church and other parts of the campus left.

But when I listen to, you know, the campus left at large,

I hear their echoes, right?

And I've said in columns that I can see

where the campus left is coming from.

I'll take elements in the campus left

over this sort of arid, you know, just make sure

you get an investment bank job, and so on.

But it's still gone a long ways away from the beginning.

And, I mean, to me, as a Roman Catholic I obviously think

Emserson has strayed a little bit far from the truth

to begin with.

But he was still within hailing distance.

- But there's a zone, (audience laughs)

there's a zone of those who inhabit the legacies

of Athens and Jerusalem that goes far beyond

Roman Catholicism,

it goes far beyond what I stand for.

And somebody like Dewey is someone who

takes seriously the Socratic legacy of Athens

in terms of centrality, of self-examination,

of self-interrogation.

He takes very seriously the hesed that flows

out of Hebrew scripture in which you attempt

to spend love and kindness to the orphan

and widow and fatherless and motherless.

But it is in a secular form.

But that's not technical mastery.

That's a critique of technical reason.

That's the critique of instrumental reason.

Dewey's is often perceived, and he's created,

he's appropriated by technocrats,

the way Leo Strauss was wrongly appropriated

by a whole lot of neo-conservatives.

And they don't like the Nietzschean dimension of Strauss,

well, that's another issue.

But the point is Dewey, I want to rescue Dewey here.

I don't want my dear brother Ross's view to be

widely accepted tonight.

(audience laughs)

Of John Dewey in terms of critic of technological culture.

He's looking for human beings who are shaped,

who will become critical citizens tied to public life.

And as a secular person who's roots flow

directly out of Christianity.

- I mean, I think that a lot of left-wing

protest politics today, there is a sacralization

of victim groups in human history

that has clearly a religious element.

But I think that it's.

I think it's ultimately incoherent

and kind of a dead end without that theological substrate.

Because in the end, the historical victim group,

whether it's black or gay or female or transgender

or any other group is not in fact, you know, Jesus Christ

died for our sins, right? - Oh, absolutely, I agree.

- It's just another fallible human group that's just

as capable of any group of taking over power

and scapegoating and oppressing in its term.

So if you're trying to sort of do Christianity

without the Christian foundation,

not that Christians have done it that well

with the Christian foundation,

(audience laughs)

but I think you end up sort of,

you're more likely to end up repeating

the same cycles of power and domination

when you yourself take power.

- So you are both graduates of Harvard University.

And Harvard University has this bold, succinct slogan.

Veritas.

- He was three years, so.

- Okay. (Dr. West laughs)

- And you can tell.

- The slogan of that university is veritas, truth.

And we at the University of St. Thomas have

recently adopted, as a Catholic university,

a different slogan, all for the common good.

How would a university that's striving for the common good,

how different should it look than Harvard?

Should its administration, should its faculty,

should its staff, should its student being doing

something different than they would be doing at a university

who's slogan is truth?

- Hmm, you want to grab that one?

- Well, I'll just say in defense of Harvard

and its antiquity, the original slogan, I believe,

I may be getting this slightly wrong.

But the original slogan of Harvard was

veritas pro Christo at ecclesia, I think.

Which is truth for Christ in His church.

And we sort of slept the Christ

and its church business away. (audience laughs)

But I do think that that slogan has a little bit

of a different valence, because it is suggesting that truth

is in, the pursuit of truth

is in the service of something else.

And I guess my take, in a way, is that you want both.

You want, especially the elite university that sees

itself sort of self-consciously educating

the leaders of tomorrow to be both sort of focused

on the actual pursuit of truth.

I think there is a danger in saying that your university

is just about sort of, you know,

that we've, and I'm not saying St. Thomas does this,

but there's a tendency to, I think, abroad

and in certain academic environments to say,

well, we've all agreed on what the common good is.

And it's something that probably happens to align

with a certain set of left-wing perspectives.

And so, the purpose of the university to further that.

And then you're sort of shunting a core mission

of the university over to one side.

You're saying, well, we've answered these basic questions.

We don't need to debate them anymore.

That's not with the university is for.

At the same time, you don't want a university

that since it is supposed to be educating people

for the world, you don't want it to be

so abstracted from that world that it's just,

you know, people reading too much Foucault.

(audience and Dr. West laugh)

Or people sort of wandering into, going deep

into their laboratories and never coming out.

Pick whatever example you want.

So I think the ideal university would put the two together.

You would see yourself as educating people

for public service.

You would have, and you would see your academics

as being committed to the pursuit of truth.

And you would have an open-ended understanding of what,

you'd want an open-ended understanding of public service

that somehow wasn't so open-ended that it collapses

into the whole, well, I'm only gonna be a consultant

for four or five years, and I'm gonna make my money,

and then I'll do something important for society with it.

You don't want to collapse to that point,

which is might be where some universities have ended up.

- No, I'd agree with brother Ross.

I think both institutions began with

what I would call a commitment to soul craft,

which is ways in which you shape persons connected to,

it could be pagan cardinal virtues of temperance

and prudence and justice and courage.

Or in a Thomistic context,

and of course Thomas's so rich complicated profile

and fascinating, not always right, but that's all right.

That fusion of theological virtues of faith and hope

and love.

And so, when you say all for common good,

that presupposes a certain kind of soulcraft.

And what's wonderful about Catholic universities

in this particular moment of cultural decadence

is that the students are forced to come to terms

with some of the greatest minds in text

in the philosophical and theological tradition

that were concerned about soulcraft.

Now, we don't do that at Harvard.

Harvard dropped off the latter section,

and Harvard became a much more corporatized university

for ruling class formation.

Now, it still has wonderful people and wonderful graduates

and so forth and so on.

But, (audience laughs)

- And professors.

- The Thomistic tradition as University of St. Thomas

says, look, we're not in this for ruling class formation.

We're concerned about soulcraft.

We're concerned about the cardinal virtues.

We're concerned about the theological virtues.

And we're gonna talk about it if it's outdated

and antiquated in the 21st century,

why?

Because it's the right thing to do.

It's the right thing to do. (audience applauds)

It's not just about money.

It's not just about cashing in.

- Give me your thoughts as a theologian on sex.

And more specifically the question of,

I mean, this is basically the line

ultimately that divides the religious left

and the religious right,

I feel like more than anything right now.

That people on my side of the divide feel like,

you know, that basically on the religious left,

there's a sense that economic,

left-wing economics goes hand in hand with a 90%

or at least 80% embrace of the sexual revolution.

Not sort of the

commodification side of it. - Right, right.

- Not maybe a pornified culture.

But the basic idea that the way we thought about

issues around premarital sex, divorce,

ultimately homosexuality and so on

are just out of date and need to be rethought.

And the Holy Spirit is speaking and doing something new.

And it seems to me that that,

I don't know even know exactly what the substance

of my question is, but I just think

it's worth talking about because it seems like that's,

and my question for you, when you think about sort

of the views of, sort of, you know,

most left-wing Christians in this country,

and you think about sort of the bulk of the Christian

tradition going back to the Bible itself on sexual ethics,

how easy do you think it is to reconcile the two?

Do you think that people on my side of the line

are missing something obvious?

It should just be easy to reread, in the Catholic context,

Jesus on divorce as not saying exactly what

He seems to be saying.

To reread St. Paul on homosexuality.

I didn't mean to bring up Francis here at debates.

But, I mean, are we, I guess, yeah, what are we missing?

'Cause we look at your side and say,

you seem to be leaving something behind.

- No, it's a wonderful question.

I've never been asked that question in public.

(Lisa and audience laugh)

I appreciate that, though, brother.

I appreciate that.

Very much so.

We talk about it, okay, as seminary, divinity school,

philosophy departments and so on.

But my read has always been this,

that first we have to proceed with an unconditional love

for each person made in the image and likeness of God.

That begins our trans, that's bisexual, that's gay,

it's lesbian, it's straight and so on.

And that's very important because you don't want hatred

to play such a role that you can't have a conversation

with the required vulnerability.

Because I don't, these are (audience members clap)

very, very difficult and delicate issues.

And you have to have an openness.

And you can't have an openness without vulnerability.

But the vulnerability is trumped to foreclosed

if you don't have this sense of persons

who are in the conversation

respected, even if you have these very deep

fissures in the certain sense.

I proceed on the notion first of I thou.

I think Buber and the others say,

how do you ensure to the best of your finite fallen ability

an I thou dynamic with the person you are with?

Because I can't go with the notion of, well,

because you're married.

But it's still I it

that thought that's all right.

And yet there's an I thou outside of marriage

that has more spiritual integrity

than some folk who are in the institution.

I say, no, that strikes me as pomp, circumstance,

where's the spirit?

Too much letter, not enough spirit.

And you can imagine, my conservative brothers and sisters

say, oh, west is started to slide down that slippery slope.

(audience laughs)

- We love our slippery slopes.

- Oh, and I do understand that because I understand

this brother Rob and George, yourself,

and the others who I love to learn from.

And challenge and be challenged,

that I do understand that you all are concerned

about, not just the society,

but you are concerned about the individuals

and the kind of integrity that each individual has within

an institution of marriage.

But that to me is very important.

That's very important.

And the question becomes,

how do you preserve that when you also talk

about other kinds of relations?

Same sex, trans, or whatever it is, you see.

And I do believe that as important as scripture is,

that there are certain hermeneutical limits

in its application to late modern circumstances.

- But if I turned around and made that argument to you--

- Yes.

- --about Donald Trump's business practices,

if I said to you, look,

the Bible talks about the widow and orphan,

the Bible is hard as anything on usury,

and, you know, all of these things, but in late modern,

late modern context, you have to take a hermeneutic

that represents the fact that the way Donald Trump

made his money is part of the machine

that raises all of our living standards.

You would have some strong words for that hermeneutic,

wouldn't you? - Yes, I would, because that

argument would consequentialist and utilitarian

but what brings you and I together,

we are deontologists as Christians.

- Mm-hmm.

- We're not concerned just what the consequences

and the effects are.

We're not utilitarian in that way.

Let Peter Singer have that, you see what I mean?

Let the utilitarians have that.

- We can agree that we're against Peter Singer, yes.

- Absolutely. (everyone laughs)

Absolutely.

You see,

oh, indeed.

Absolutely.

But I think what I mean by limitations is that, one,

there's a difference between Ptolemy and Copernicus, right?

There's a difference between slaves obey your masters.

And we're all anti-slavery.

There's a difference between not wearing certain kind

of color on your clothes.

There's a lot of things in the Biblical text,

let alone the violence and genocidal moments.

What does the Exodus look like

from the Canaanite point of view?

What would Amos say?

What would Isaiah say?

What would Ester say?

Oh, even these Canaanites

have a humanity.

Well, it didn't work out that way.

Well, no, it didn't.

I mean, I'm just raising some questions.

I'm not saying I'm coming up with any answers here.

But this is precisely the kind of zone

of vulnerability that is required in order to see

where some of these fissures or gaps

or hiatuses really reside.

And I do think there's a certain sense

in which conservative brothers and sisters

and myself, and I call myself a preservative

rather than conservative, (audience laughs)

because I want to preserve all whole lot of the tradition.

But conserve, too often that is an accommodation

to status quos that I'm very critical of.

See what I mean? (audience members clap)

And so, the question becomes then,

where is that overlap preservative and conservative?

And times there's just this fissures in the road

and you can't in the end be able to bridge it.

We still love each other, but we can't bridge it

at a certain point, you see.

- I guess when I look at our culture--

- Yes, yes.

- --I see that sort of sex, right,

in all its many forms is bound up

in just a lot of the sort of broader cultural trends,

commodification, everything else that you decry.

- But not sex as cause, but sex as consequence.

The market is really the source of the commodification,

right, it's not the sex, per se.

- You know, the market's very powerful, right,

because the market precedes from human greed.

But sex also precedes from a very powerful human

impulse, and I guess-- - But depends on

what kind of sex.

It depends on what kind of sex, now.

I thou, I thou that sex I would never call greed.

But I thou sex is not greed, though.

That's a sharing of vulnerability

and a magnificent joy that flow from pleasure.

- Well, what am I supposed to say to that?

Come on. (audience applauds)

- But, yeah, I vow is something else.

I it, manipulation, domination,

squeezing out certain kinds of titillation,

oh, my God, that is spiritually empty.

We agree with that?

- We agree with that.

- Absolutely.

- I am just so thankful Mr. Douthat that you raised

the sex question because-- (audience laughs)

- People always say that to me.

- --I would not have dared to do it.

- [Man] My name is Nathan Delgado.

And I represent my community and Ujamaa Place.

My question is focused around perpetualism

and control of the mind.

If Africa, when it was a continent called Ethiopia,

was conquered by the Roman Africana,

and we today call ourselves African Americans,

are we perpetuating some kind of power structure

by white supremacy.

- Just by the name itself?

- [Nathan] Say it again, brother.

- You mean just by the name itself, though, brother?

- [Nathan] Yes.

- Oh, well, you know, it's such a historical leap,

though, to go all the back to that particular historical

moment you just invoked and then come right in to

the new world, the U.S. experiment,

slavery and so forth and so on.

- [Nathan] Time, just a time crunch.

- Yeah, exactly, so the issue of, you know, names

are very, very precious, but fragile things.

They mean much to us in biographical time.

In historical time over long periods of derase,

there's so many mediating factors, my brother,

so that the question becomes for me,

it's less the name and it's more

the deed, the action, the life lived.

I am much more in loved with Negroes

named Martin Luther King, Jr., than these post modern

Afro Americans who got a fancy name

but too cowardly to really wanna fight.

See what I mean? (audience applauds)

So, whatever you call yourself, that's fine, work it out.

Let's see what you gonna do on the ground.

That's what I want you to see.

(audience applauds)

- Mr. Douthat, do you want to,

do you want to pitch in?

- I mean,

(Dr. West and audience laughs)

so many perils.

Um, (Dr. West and audience laugh)

the Negro National Anthem does sound better than

Afro American National Anthem.

- Absolutely, Negro lift every voice.

That's Negrosity right there.

- Yeah. (audience laughs)

I guess I would just say,

my view is that you get further

by reclaiming forgotten parts of the past

than by trying to rename and erase

things that have had those names for a very long time.

So, you know, I'm generally against, you know,

the sort of,

yeah, I mean, it's complicated.

It's like Yale University just went through this whole thing

over Calhoun College. - Calhoun College, yeah.

Exactly, exactly. - You know, and Calhoun

was a brilliant philosopher,

brilliant political philosopher

and incredibly important American statesman

and a horrifying racist who did more to sort of

instantiate the view that slavery was here

to stay than a lot of other figures.

So I could see the case for renaming Calhoun College.

At the same time, you know, if you look at sort of what's

going on in debates about sort of the south

and confederate memorials and so on, my view is that,

you know, if in the entirely imaginary world

where I were black or African American,

I would be much more interested in getting

to the point where you have, you know,

more memorials to slavery.

More, you know, you can go to the south

and go on actual plantation tours.

There was a story in the Times about one

of the only places where there's this sort of serious museum

of plantation life that really brings into what,

you know, what plantation life meant for slaves.

It isn't just for tourists to have their moonlight

and magnolia's thing.

That to me seems like

a more important priority, put out new statues

rather than figuring out how to sort of,

those confederate statues are part of the southern past,

it's part of the reality.

And, yeah, so again, as an outsider in many ways

to these debates, I think that there is more

to be gained by recovery than by erasure

and abolition of what realities of the past was.

- [Man] My name is Mahmoud El-Kati.

- Yes, yes, yes. (audience applauds)

- [Mahmoud El-Kati] I contend.

And in the western experience,

what functions as a religion

is the ideology of white supremacy.

I'd like for you to address that.

- Mmm.

Mm-hmm, nah, appreciate the question.

And the white supremacy is not just black people.

It begins with our precious indigenous peoples.

It begins with our precious indigenous people.

(audience applauds)

And we know they don't have to be in the room

for us to acknowledge them.

And, of course, you all have the rich tradition

of de las Casas and the others in the Catholic,

in the Catholic word that brought tremendous critique

to bear on the violation of humanity

of indigenous brothers and sisters

in the name of

an understanding of Jesus mediated

with a Catholic tradition.

So you got resources in that record.

But it's brown, it's yellow.

Black white is the central one.

Why?

Because rage has always been the major threat

to the white supremacist status quo.

So you gotta keep more time keeping track of Negroes

than you do of indigenous people.

They own a reservation, and so forth and so on.

There's not enough browns yet.

You can push the Asians out as you did with the Chinese

with the Exclusion Act in the 19th century,

but they don't surface in the public imagination

the way black people do.

But spiritually and morally speaking,

each particular group has the same significance.

And, of course, they say, oh,

what about black people being racist against white people?

That's wrong too.

Of course it's wrong.

But there's no institutions,

there's no structures of black supremacy

that reinforce (audience claps)

the reproduction of that.

You see?

And you say, well, what about the NBA.

Okay, well, that's different.

(audience laughs)

Owners still white, but the talent, we understand.

(audience laughs)

- I disagree in my peril, but I think that's

too, I think the way the term is used is too capacious.

- Too broad in its application?

- Yeah, I think there is a particular historical

relationship that is distinctive to the United States

between the slave owning population and black slaves.

And that, I think, deserves to go by the name

of white supremacy and it is distinctive.

It is the relationship of people who owned people

to the people that they owned.

And it is connected to incredibly particularist forms

of social development in the African American community

related to slavery.

It's connected to sort of particularist anxieties

and fears in the white community related to slave revolts

that sort of have echoes down to the present day.

And I think that's different from the complicated ways

that races and classes have related to each other

in the U.S. and in other situations.

I don't think the position of Hispanics in the U.S.

is today is really that relatable to the

historic position of black people.

I can see political reasons why for the purposes

of alliance building, people on the left want to make the

argument that they are.

But the Hispanic experience in the U.S.

has more in common with the Italian and Irish experience

in many ways than it does, not in many ways,

it just has a lot more in common.

We've never enslaved Hispanic people.

We treated them, Hispanic people have been treated badly.

They're exploited, they're exploited in the ways

that immigrant populations--

- But what about the land grabs in Texas and California?

- Yeah, but that's not the same as chattel slavery.

- But I'm just saying, I think there's, you were talking

about the darkness in the human heart.

You look around in human history,

human beings are always dividing each other by lines

of tribe and attacking each other and exploiting each other,

persecuting each other and so on.

And within that landscape the experience of immigrants

in the U.S., the experience is different

from the experience of Native Americans,

and this sort of ideological foundation.

White people in America treated American Indians terribly.

We conquered them.

We took their land after we, mostly accidentally,

but occasionally on purpose infected them

with terrible diseases.

But our intellectual relationship to Native Americans was

totally different from our intellectual relationship

to black people because they are our enemies

that we were fighting against.

So there was this whole tradition.

There's a reason that we ended up,

we have all these debates about Native American

mascots, right, for sports teams.

We have those debates because white people had this image

of the Native American as this impressive,

noble enemy who we warred with.

That's totally different from the cultural relationship

that my ancestors had with your ancestors.

- You wouldn't use the language of white supremacy, though,

even though it is, in relation to indigenous people,

even though it's very different than black folk

and different than others, it's still white supremacy,

though, isn't it?

- It's just-- (audience applauds)

- Or what kind of language would you use?

- Well, I mean, what language would you use to describe

the relationship between the Hutus and the Tutsis

in Rwanda, right?

- Yeah, right, right.

- There are two ethnic groups, and white supremacy factors

in because you have colonial leaders coming in

and measuring people and saying, well,

this group is more like us, so it's affected by that.

But those kind of conflicts are endemic

to human affairs all over.

The relationship between, it's like,

my ancestors are from the British Isles originally.

Right, the British Isles are one people coming in

and one conquest after another, right?

- We can and our Irish brothers and sisters about that.

- Well, right, but is the relationship between

and racism factors in and so on, but would you say

that the relationship between the English and the Scots,

I have English and Scottish ancestors, right.

My English ancestors ravished, cleared,

drove my Scottish ancestors off their farms.

You drive the Scottish highlands today,

it's not a genocide, but it's all sheep where

there used to be people, because people in the 18th century

came through and forcibly moved people off the land

and killed a lot of them.

Is that, that seems to me to be, you know,

a more analogous to some of the conflicts

between American settlers and indigenous populations here

than it is to chattel slavery.

So I think this is, I'm not trying

to be the conservative who's creating divisions

on the left-- - I think you're rightly

showing the varieties of forms of domination

and the fact that we should not confuse and conflate them.

I agree that.

I agree with that whole heartedly.

I'm just wondering why you would be reluctant or hesitant to

want to use white supremacy

in these other cases. - Well, look at Europe today.

Right, so what's going on in Europe?

Europe is convulsed with anxieties about Muslim immigration.

- The others too.

- Right. - Yes.

- And that is connected to race and racial issues

and European parties are conflating anxieties

about Muslim immigration, with anxieties

about black Christian immigration

from sub-Saharan Africa and so on.

But I hear people on the left say, okay,

what Donald Trump is talking about when he talks about crime

in the inner cities.

That's why supremacy.

And what European conservatives are concerned

about with Muslim immigration, that's white supremacy.

And I say, these are not the same things.

The story of Christian Europe's relationship

to its Muslim neighbors is a totally different story,

with incredible swings and balances of power

on both sides with with a real huge religious

and theological core of difference that creates

a specific set of problems.

Whereas, in the U.S., historically, white people

and black people had the same religion.

And yet the white people were enslaving the black people.

- We had different interpretations.

- Well, right, but there's, - But right.

- But there's a theological common ground

between what became slave religion

and religion of the masters, and it just seems to me.

Again, when I hear people say, well, you can create

this category and say, okay, what happens when Christian

Europe, once Christian Europe confronts Muslim immigration

is the same thing as what happens in a country like ours

which had this incredibly finely enforced color line

around race, but they don't seem to me to be the same thing.

The have some commonalities.

But anxiety about an Islamified Europe is not rooted

in the same fears as the anxieties

of the master class in the south.

They're just not.

- No, I agree with that, I agree with that.

I don't want sameness, I want specificity

and distinctiveness, but I can still apply a category

in each circumstance and see how its articulated

in different ways relative to those circumstances.

- [Woman] Hello, my name is Xiomara Guzman.

I am 16.

And my question is for Dr. West.

What advice would you give to our current youth

more on my age spectrum, where racism, discrimination

and xenophobia feel more prevalent

under this Trump administration?

- Oh, I wouldn't be obsessed with Trump.

Don't fetishize him, don't give him magical powers.

He's gonna come and go.

The crucial thing for you, my dear sister, at 16 years old

you got a whole life to live.

And you commit yourself to a vocation of striving

for spiritual and moral excellence

in the life that you have.

So you enact an integrity and honesty and decency

and courage that puts a smile on yo grandmama's face.

(audience laughs and applauds)

That's what we talking about.

That's what we talking about. (laughs)

- I mean, I wasn't, put I'll,

I wasn't asked, but I'll offer anyway.

(audience laughs)

- Absolutely.

- I agree with what brother West said.

And I think it's useful to remember, you know,

that real life is not the Internet.

And the Internet, it is a magnifier of anxiety.

And I'm not saying that you should not be anxious

about the presidency of Donald Trump.

I've written many columns expressing my own anxieties

about the presidency of Donald Trump.

I'm not saying that you shouldn't be anxious about racism

and discrimination and every form of evil in the world.

But you should be most anxious about them

where they affect your real life, where you really live.

In your family and neighborhood and community.

And if you encounter those things in your family

and neighborhood and community,

you should dedicate yourself to fighting them.

But there is a temptation to go out

and seek out virtual experiences that confirm

your anxieties and magnify them in ways

that don't reflect the reality of everyday life.

And the reality of everyday life is that America

in the year 2017 is decadent.

That is a word that you and I

can certainly agree on. - Do agree on that actually.

Flawed, fragmented, split apart in all kinds of ways,

corrupt in all kinds of ways,

but, you know, most periods in human history

have featured evils and corruptions greater even

than the ones that we confront now.

And people in those context have found ways

to live their lives heroically and bravely and courageously

without falling into a palsy of anxiety and victimization

when bravery and heroism are what's actually called for.

That is a better way (audience applauds)

to live.

- Absolutely.

Absolutely.

- It's a hard way to live on here sometimes,

which is a case, I think for whatever else you do

in response to the Trump presidency,

live as fully as you can in fleshed reality

whenever the opportunity presents itself.

And there I've brought us back around to that

sexual ideas, I guess. (audience laughs)

- Thank you all for coming, and please join me.

I think that we have had a phenomenal example

of the kind of dialogue I wished we had in the rest

of our country these days.

We are taping this, I want to send it

to everybody in Congress.

I would like to show them (audience and Dr. West laugh)

how we could talk and how we should talk

to one another in order to address the very real challenges

that we have in front of us.

Please join me in thanking our two brilliant speakers

for their conversation.

(audience applauds)

- [Dr. West] Oh, man, it was wonderful, brother.

I appreciate it. - It was fun.

For more infomation >> German Army Searches Barracks for Nazi-era Memorabilia - Duration: 1:01.

For more infomation >> German Army Searches Barracks for Nazi-era Memorabilia - Duration: 1:01.

For more infomation >> Baby Doll Bath Time Learn Colors with Surprise Eggs Video for Kids Nursery Rhymes for Kids BDTKSE - Duration: 5:05.

For more infomation >> Baby Doll Bath Time Learn Colors with Surprise Eggs Video for Kids Nursery Rhymes for Kids BDTKSE - Duration: 5:05.

For more infomation >> İclal&Fırat | [Everything I Do] I Do It For - Duration: 3:16.

For more infomation >> İclal&Fırat | [Everything I Do] I Do It For - Duration: 3:16.

Không có nhận xét nào:

Đăng nhận xét